|

Reviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

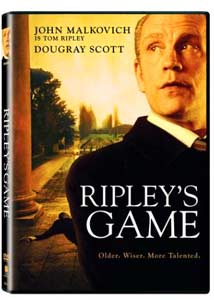

RIPLEY'S GAME

This riveting movie comes across as more genre-conventional than Anthony Minghella’s

acclaimed literary take on The Talented Mr.

Ripley, the first of Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley books. In both instances, director Alfred Hitchcock’s oeuvre is evoked, not least by the fact

that a Highsmith novel also provided the basis for Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train

(1951). Though Minghella’s film, a neo-Hitchcockian revisionist/homage, brings to the surface

the themes of homoeroticism and obsession that are an undercurrent in many of Hitchcock’s

films, Ripley’s Game confines itself within the pulpy entanglements of the thriller genre.

Set in the present day, years after the events of The Talented Mr. Ripley, Ripley is

now mostly retired from his criminal lifestyle, happily married and living in Italy. Before too

long, though, he is visited by Reeves (the great Winstone), a figure from his past, who pleads for

Ripley’s help in murdering a Russian mobster. Pretty soon, old rake Ripley is back to his devious

tricks.

Because of the character’s desperate need to be liked, the Ripley in Minghella’s film (played by

Matt Damon) is more vulnerable and sympathetic, ultimately racked with guilt at the horror of

what he does to prevent the discovery of his crimes. Here, Ripley has evolved into a more

fastidious creature, seemingly caught up in the health craze and wearing fashionable silk ties and

berets, all the while dispensing hilariously droll one-liners, delivered by John Malkovich with

inimitable gusto. As played by Malkovich, it is clear that Ripley has gotten more confident and

self-assured with age. Indeed, the actor has a particularly creepy soliloquy in which he ruminates

on his lost conscience that perfectly encapsulates the reason it is not as easy to identify with this

new incarnation of Ripley as it was with Matt Damon’s.

This distancing of the viewer from the character is not necessarily a flaw, and may even be

appropriate considering the specific plan Ripley has in mind. In a development similar to that of

the premise of Strangers on a Train, Ripley comes up with the notion of having a person

totally unrelated to the proposed victim - and therefore beyond suspicion - kill him.

Another major difference is that Ripley’s Game is more

concerned with thrills and shocks. Minghella’s film - due to its inherent anxiousness as to

whether Ripley’s real identity will be discovered - is more intrinsically suspenseful, as opposed

to shocking. Though there are some scenes in Ripley’s Game that contain elements of

pure suspense similar to that found in both Minghella’s film and the best work of Hitchcock

(such as a sequence aboard a train that is strangely, and perhaps intentionally, comically

reminiscent of the stateroom scene in the Marx Brothers’ 1935 A Night at the Opera).

The thrills mostly come from nervously anticipating what the next move of Ripley will be. In this

way, the film seems to be driven more by its premise than anything else – which might be why

Ripley’s motivation remains too ambiguous, and why what could have been a much more

suspenseful ending is muted by the viewer’s lack of knowledge into Riley’s character.

This is not to say that this film is inferior, as a whole, to The Talented Mr. Ripley –

merely that it functions in a different mode.

What Ripley’s Game understands quite well, however, is a trait that made Hitchcock’s

films so effective - not directly addressing all of the themes involved, and instead leaving them

open-ended, if not ambiguous, in favor of economical and efficient screenwriting. This is clear in

an extremely subtle manner during a scene late in the film (hint: it involves Reeves). While I do think the Master of Suspense would have appreciated the tone set in The Talented

Mr. Ripley, I also think that - were he alive and working today - he would have preferred

the knottiness of the plot in Ripley’s Game. Reymond Levy

|