|

Reviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

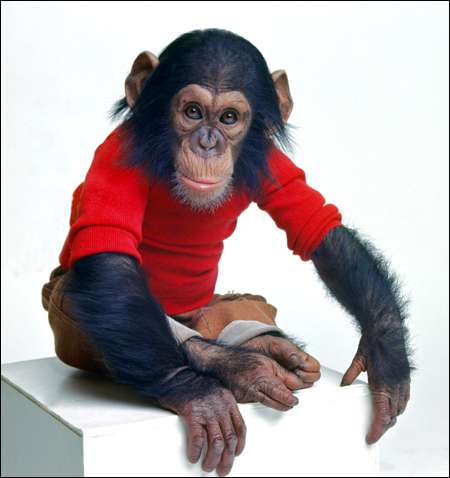

PROJECT NIM

In 1973, Nim Chimsky was forcibly removed from his tranquilized mother at a primate studies facility (a scene that’s ominously reenacted) to become the guinea pig, so to speak, for Columbia University behavioral psychologist Herbert Terrace, who was investigating how language evolved. In an examination of the nature vs. nurture theory, could Nim learn how to communicate with language if he were brought up like a human? At two weeks old, he became the tenth member of the Upper West Side academic household of Stephanie LaFarge, Terrace’s former student and lover, who raised Nim as if he were her newborn. Among the film’s uninhibited talking-heads confessionals, LaFarge admits that she had never studied chimpanzees, no one in her home knew sign language (which was crucial for the study), nor did she ask her family for permission to care for Nim. (In a battle of the alpha-males, Nim took an instant dislike to her husband and defied him—chimps are raised by their mothers only.) Like a teenager, he liked alcohol, wouldn’t refuse a toke, and masturbated—a lot. As Terrace puts it, LaFarge wasn’t concerned with discipline. Cue the arrival of Laura-Ann Petitto, an undergraduate hired to become Nim’s babysitter and teacher. According to her, Nim needed a “neutral, soothing environment,” and Terrace abruptly removed Nim from the LaFarge home to a rent-free mansion on an idyllic 28-acre Riverdale estate, where the chimp would reign supreme—for the moment. (In a sign of New York real estate values of the time, the leafy Columbia University-owned property was then vacant. It has since been converted to an upscale housing development.) As a baby, Nim is adorable and mischievous, and as an adolescent, equally as playful—but at turns vicious, and not always predictably. (Director James Marsh has been blessed with tantalizing archival footage of the chimpanzee.) Yet this is one animal-centered film where the human antics steal the focus from the critters. You might expect the film to be a little bit like Born Free or even have shades of a science-fiction admonition, but similar to The Ice Storm—the Ang Lee film and Rick Moody novel of imploding Northeastern families where traditional values are also shaken and turned on their head? It is impossible to separate the events exhumed in this documentary from the experimental, free-spirited, and laissez-faire mood of the era. The film raises innumerable questions, some scientific but most involving the actions of Nim’s caretakers. (Terrace calls Nim a brilliant beggar, while expressing disappointment at his limited use of language.) More than 35 years later, sniping between the homosapiens continue. The battle for the power seat in rearing Nim continues, now transferred to setting the record. Charges of deceit and incompetence fly, and the dry Dr. Terrace’s summations are withering. Forget the chimp nature vs. nurture angle, someone should study the humans. With such inherently compelling participants, Marsh doesn’t need to cut away so often to reenactments. Eerily, it’s hard to tell the LaFarge family photos from the mock home movies, so well does the film capture the look of the ’70s. However, Marsh’s over-reliance on music (which includes the ubiquitous Penguin Café Orchestra, heard in many a commercial) feels redundant, especially during a particularly bleak chapter of Nim’s life. At that point, the film has become harrowing enough. These are small quibbles though.

Project Nim

is an excellent example of where film imparts valuable insight by the

act of filming alone, and not necessary in what the forthcoming

interviewed subjects have to say, though there’s that too. It’s in how

they convey their interpretations of the past that’s most

revealing—including their pauses. A casting director couldn’t have done

better job in finding an intrinsically diverse and compassionate (for

the most part) ensemble.

Kent Turner

|