|

Reviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

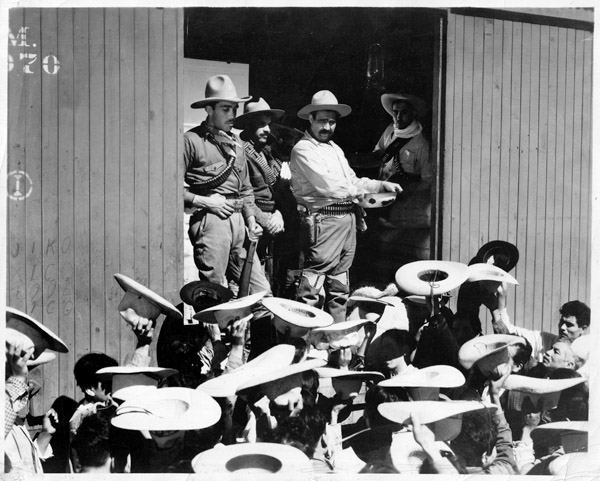

2010 NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL MASTERWORKS The New York Film Festival’s annual Masterworks series showcases retrospectives of classic films rarely seen in the U.S., while commemorating two anniversaries. The centennial of the start of the Mexican Revolution, 1910–1918, is being marked with writer/director Fernando de Fuentes’ 1930’s trilogy (in addition to Revolución in the festival’s main section, comprised of short films by 10 of Mexico’s leading contemporary filmmakers). Even with censorship problems and nods to period conventions of melodrama, these three perspectives reflect more the complexities of the social and political upheavals caused by the revolution than nationalistic propaganda. Prisoner 13 (1933) cynically illustrates the moral corruption in the military. The lives of political prisoners are bought and sold by a drunken colonel who (conveniently) learns his lesson in the nick of time. With visual jokes like the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup a year earlier, My Buddy Mendoza (1934) amusingly satirizes a fence sitter during the revolution, a land owner who alternates between sucking up to General Victoriano Huerta’s army and generously supplying the rebellious forces of Emiliano Zapata. Even in a comedy, a side finally must be chosen. Let’s Go with Pancho Villa (1936) brought Mexican filmmaking into the global ranks, with a closing scene as similarly haunting as in Mervyn LeRoy’s I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932). The film visually and thematically recalls the battles and disillusionment in Lewis Milestone’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) (with more horses and packed trains). Five peasants from the same village, young and old, become favorites of the revolutionary leader, but one by one they find that being his “lions” comes at an excruciating price. The “Elegant Elegies: The Films of Masahiro Shinoda” sidebar is part of the city-wide celebration of the 150th Anniversary of the first formal contact between Japan and New York, when visiting samurai were feted in the streets. In the first American retrospective of his films in over 35 years, twelve films from this key figure in Japan’s New Wave demonstrate Shinoda’s pessimistic range, from postwar alienation to historical analogues.

Pale Flower (1964, being shown in a new

print) is an early black-and-white noir tour through the yakuza

underworld of serious gambling and careless retribution that give a

charismatically brooding ex-con and a pretty, irresistible dilettante cheap thrills.

Shinoda himself will

introduce the screening on Saturday, September 25.

Adapted

from a famous novel by a leading Japanese Catholic writer,

Silence (1971) is set

during the 16th century of religious persecution of

Christians. European missionaries try to restore contact with a

stubborn sect that has kept faithful in their fashion. Its vivid and

intensely philosophical portrayal of individual responsibility under

brutal torture and brainwashing has a very contemporary resonance

regarding the combustible intertwining of religion and politics. Martin

Scorsese fans will want to see it—he’s working on a remake.

Nora Lee Mandel

|