|

Reviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

THE 47TH

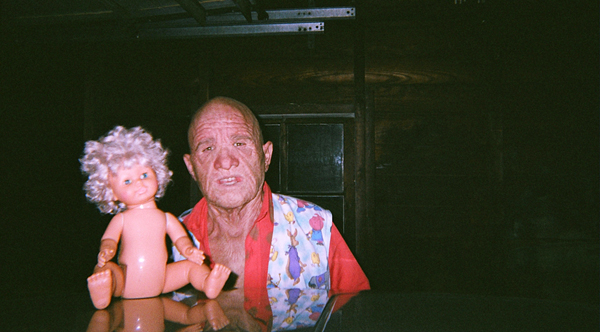

NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL Every festival has one—the WTF film that drives audiences toward the exit sign. In programming Harmony Korine’s raw Trash Humpers, the New York Film Festival stakes its claim as a curator, leading audiences to something they most likely would overlook or avoid. The NYFF is nothing if not consistent, championing a director whose Gummo was labeled the worst film of the year in 1997 by Janet Maslin of the New York Times. But there are no dead grandmas or cats here, just murder, mayhem, and masturbation. Take the title literally. Never have so many curbside trash containers been violated in the name of art, as well as trees, a mailbox, and a forlorn electric pole. Trash Humpers looks like a discarded, homemade VHS recording of the ramblings and ravings of two men and one woman wearing old people masks. They look almost nonhuman, like Mandy Patinkin in Alien Nation.

Two other NYFF veterans return in their strongest efforts yet (and like the other films mentioned here, they have no US distributor as of yet). Their inclusion lives up to the festival’s mission of picking the crème of the year’s art-house crop. White Material may be the closest Claire Denis comes to making an action film. As intimate but far more intense than her most recent films, she and cowriter Marie NDiaye ambitiously draw upon a larger canvas: an unnamed African coming apart as a rebel army, armed with child soldiers, takes over the countryside (with shades of the recent conflict in Uganda). A refreshingly subdued Isabelle Huppert stars as a stoic Marie Vial (but keep in mind that with Huppert, her steely façade is bound to crack). She heads a struggling, family-run coffee plantation all on her own. Her workers have fled, heeding the warnings of the French Army of advancing rebels, but all Marie needs are five days to harvest the coffee beans. The film’s point of view is scattered and to the point. This is Africa seen through the white bourgeois, the black elite, and children with machetes. It’s also the rare film about Africa that doesn’t allow the beauty of the land to overwhelm or apply a glossy sheen to the story. With many tense scenes of discomfort (both for the characters and the audience), Bruno Dumont has painted a lucid and startling portrait of ego run amok crossed with absolute religious fervor in Hadewijch. The title refers both to the 13th century Dutch mystic and poet (and allegedly nun) and the young, 21st-century novice (née Céline) who painstakingly follows in her namesake’s footsteps. Punishing herself, Hadewijch goes without warmth or food, barely eating a scrap of bread. (The soft-spoken, baby-faced Julie Sokolowski looks like she stepped out of a Giovanni Bellini painting.) Despite all the outward signs of devotion, her mother superior sees otherwise, calling her a caricature of a nun with a “high degree of self love,” and recommends that Céline return to the world outside the convent. At first, we have to take the mother superior’s word, but we know that Céline’s a bit odd because of what she says and, later, commits. She puts off the advances of a would-be boyfriend declaring, “I love Christ. I’m for him.” Later, during prayer, she whispers, “The sweetest thing about love is its violence.” Oh, oh.

There’s nothing sadder than a circus performing to an empty tent, as in eighty-one-year-old New Waver Jacque Rivette’s Around a Small Mountain. Somehow it’s even sadder when the one audience member laughs, taking the clowns, unused to any response, by surprise. That would be Sergio Castellitto, as a well-to-do roamer who stays in a small provincial French town for a week just to see a family circus on its last leg. Eventually, he becomes part of an act, and delves into the romantic and personal entanglements of the troupe. The film begins promisingly, almost dialogue free, but then the actors start to yak. Actress Jane Birkin’s reactions and supple physicality bring to mind Guilietta Masina, even before we find out that Birkin plays a former circus performer who has returned to the fold. But the nimbleness of the film fades when the acting turns flatly presentational. The actors, directed to face the camera, are constrained by the artificiality of the dialogue. When Birkin delivers not one but two confessional monologues, she’s in her own world, disconnected from the audience. You don’t go to the circus for speech. Unlike the other films reviewed here, this trifle is a rote choice for the festival.

Life centers on the

ironically named Joy, played by the barely there, self-effacing Shirley

Henderson, as the film’s most frightening figure, a guilt-ridden,

ego-less doormat—her wispy, high-pitched, little-girl voice

is an acquired taste. Allison Janney veers dangerously toward a sitcom

performance as Joy’s pill-popping, blindly optimistic older sister. And

as

the pathologically narcissistic sibling, Ally Sheedy overacts compared

to the serenely cool Lara Flynn Boyle, who originated the role.

Strongest in the cast, though, is Dylan Snyder as freckle-face Timothy,

who finally finds out that his father is not dead, but a pedophile sent

to

the slammer. He handles the squirm-producing dialogue without

affectation, and poses the film’s repeated question, “Maybe it’s better

to forget and not forgive.” Although Solondz sometimes strains for shock

value, there are enough subtle verbal jabs that sting. Kent Turner

|