|

Reviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

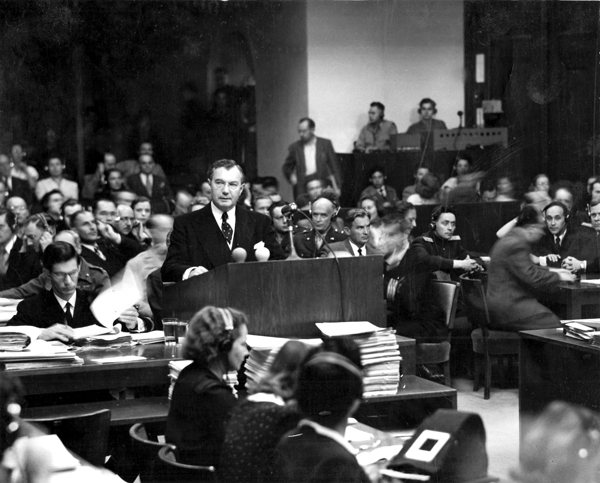

NUREMBERG The first Nuremberg trial opened 65 years ago. It tends to be specifically remembered as a post-World War II expiation of the revulsion against the Nazis and generally regarded as an international precedent for defining and punishing war crimes. Americans may have not well understood the almost year-long proceeding as a fair, formal trial of the major Nazi leaders because the film intended by the U.S. chief prosecutor to document the legal process was never shown here. The creation, disappearance, recovery, and complex restoration of the 1948 documentary, Nuremberg: Its Lesson For Today, may be even more of a dramatic story than that filmís careful presentation of the rise of the National Socialists in Germany, the four-count indictment against 21 prominent Nazis, their defense, and the verdict. Most of what is seen in the movie was presented as evidence from compilation reels of footage made by Nazi authorities or the allied forces or culled from the only 25 filmed hours of the trial. The visual documentation of the crimes and the reckoning were promulgated by Robert H. Jackson, who took leave from the U.S. Supreme Court to help set up the first-ever International Military Tribunal and lead the American legal team. The Office of Strategic Services Field Photographic Branch, charged with finding the Nazi footage, was led by director John Ford, who would film the trial. He supervised brothers Budd and Stuart Schulberg, sons of former Paramount studio chief B. P. Schulberg, in the hunt (which ranged from rescuing burning cans of film to corralling Leni Riefenstahlís help) that resulted in the trialís presentation of the four-hour The Nazi Plan and the one-hour Nazi Concentration Camps. Legendary Depression-era documentarian Pare Lorentz, then head of film/theatre/music section at U.S. War Departmentís Civil Affairs Division, commissioned Stuart Schulberg to write and direct a film that would methodically lay out the crimes and the trial as a somber lesson to a general audience. However, completing the film was complicated by internecine quarreling between the military and various government agencies during the editing (Lorentz quit, the Russians made their own version). The U.S. government showed the film only in Germany as part of de-Nazification efforts. The reasons for the limited release were murky at the time (possible Cold War re-jiggering of priorities when the Russians blockaded Berlin in 1948) and are even more mysterious now (probable commercial distributor resistance). While clips from the evidentiary and trial footage have appeared in documentaries over the years, Stuart Schulbergís family several years ago found a print of this forgotten film among their fatherís papers. The restoration by his daughter Sandra, an experienced film producer, goes above and beyond technical preservation. She teamed up with documentarian Josh Waletzky (Partisans of Vilna) to track down a better quality print in German archives and undertook the meticulous chore of synchronizing the trial scenes with tapes of the actual courtroom audio, as well as adding the English narration by Liev Schreiber. These courtroom scenes uniquely elaborate beyond the images familiar from the History Channel and demonstrate how this first Nuremberg trial helped re-establish the civilized rule of law for war-weary Europe. Many Americans view of the trials is probably influenced by Stanley Kramerís Judgment at Nuremberg, which fictionalized a later case. There are two key differences in witnessing the real thing. First, the equal involvement of civilian allied prosecutors, who each present a charge. While Justice Jackson opens with the first count of intent of conspiracy, the British prosecutor presents count two of crimes against international peace, the French prosecutor submits the third count of crimes against humanity, and, probably significant for the filmís fate, the Russian prosecutor introduces the fourth count of war crimes for atrocities against prisoners of war and civilian populations, particularly in the east. Second, unlike subsequent, perhaps more cathartic, trials in Nuremberg and elsewhere, it lacks emotional victim testimony. The very explicit evidence lies in the paper trail of the Nazisí own documents, seen on screen, and the captured film footage, with a few shots Schulberg discovered shortly after the trial. The thoughtful, systematic, and unflinching presentation of the legal case makes this film relevant as a model for bringing charges in what would later became known as genocide. (At the press conference accompanying the filmís debut at the New York Film Festival, the U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues, Stephen J. Rapp, cited a specific ruling from this case that was used as precedent recently in Rwanda.) While this

documentary is a very valuable and educational resource on its own,

Christian Delageís

Nuremberg: The Nazis Facing Their Crimes (2006) features

extensive interviews with

Budd Schulberg

about preparing the evidentiary films and the filming of the trial,

including Fordís technical difficulties in capturing the Nazis watching

the footage in the courtroom, a memorable image not included in this

documentary. That shaming would have made this film less of a lesson for

the future, though, and probably would have not fit in with Justice

Jacksonís intentions in approving the film, which matched his opening

statement: ďThat four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with

injury, stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive

enemies to the judgment of law is one of the most significant tributes

that power has ever paid to reason.Ē

Nora Lee Mandel

|