|

Reviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films

in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

New Directors/New Films 2011

Presented by the Museum of

Modern Art and the Film Society of Lincoln Center

March 23 – April 3, 2011

Overall, the slate for the 40th edition of

New Directors/New Films is wildly spotty. The program should take a

lesson from the Tribeca Film Festival: less is more. A handful of films

could easily be shed for a tighter focus so that the series really

becomes a showcase and not just a literal realization of its name. As

usual, the selections with the best buzz have already garnered top

awards around the world: Incendies was nominated for an Oscar

last month, Happy, Happy won a grand jury prize at Sundance, as

did Octubre at Cannes. However, there are a few diamonds in the

rough. Since some of the finest films from

last year’s edition—Tehourn, Northless, The

Evening Dress—have yet to be screened at your nearby Landmark

Theatre, here’s a road map from three perspectives as the films below

make their way around the country.

For a film with an original voice, it’s tough to beat Pia Marais’s droll

At Ellen’s Age. Sounds like a coming of ager for an

adolescent or a teenager, right? It is, kind of—but for a dazed

40-something flight attendant, Ellen (the bird-like Jeanne Balibar), who

has left her part-time boyfriend, may have a life threatening illness,

and has just been fired. The film’s a bumper-car of a ride, the flip

side to an Eat Pray Love-type of manifesto. The film takes

Ellen around the world, but nowhere near an idyllic resort; she squats

with kids half her age instead. She fumbles about, anchorless, not

knowing what she wants; and when she does, she still takes her cue from

others. At least she’s somewhat self-aware, admitting to a new boyfriend

that’s he’s just a bridge for her, and “nothing more.” Hand-held

realism alternates with an otherworldly, alternative world of airport

hotels—filled with the lonely and rock-star level of

debauchery—and, later, nude street theater. Ellen’s ex-boyfriend is

right, she’s sleepwalking through life, but with eyes wide, wide open.

In a scathing and crazily convoluted look at a pop culture footnote,

Australian director Matthew Bate goes back to the recent past, before

the reign of YouTube, in his twisting and absorbing self-described auto

vérité, Shut Up Little Man! An Audio Misadventure. In

1987, two college grads from Wisconsin, Eddie Lee Sausage and Mitchell

D., moved to San Francisco and lived in a dumpy apartment with

paper-thin walls next to two raging-all-through-the-night alcoholic

neighbors, one a redneck, the other a snippy queen. After the former

threatens to kill Eddie for complaining about the noise, the

Midwesterners take a passive form of revenge, sticking a microphone out

of their window and recording the nocturnal and monotonous rants. (The

title comes from one of the oft-repeated put downs. Most of the

retorts can’t be posted on a family website.) Eventually Eddie and

Mitch collected 10 hours of tapes over two years (all without a

copyright—at first) and passed them around. Their popularity reached the

point of the material inspiring a play and three competing film

projects. One producer envisioned Brando and Nicholson as the stars.

What started out as a goof is a jaw-dropping and tangled case of

copyright infringement beyond what any music sampler could imagine, and

that’s not forgetting invasion of privacy issues.

Egypt has pride of place this year with two films that are very much of

the moment. Part documentary and let’s-put-on-a-show hip-hop

celebration, Ahmad Abdalla’s angry and rowdy Microphone

heeds few narrative conventions. There’s a germ of a plot about

underground Alexandrian hip-hop and metal bands striving for artistic autonomy, but the film is mainly free form. The hip-hop

hipsters, looking for a grant from the government, face a lot of

resistance: no obscenities or English lyrics. An all-girl band appears on

camera with their faces obscured, in case of retaliation, and there’s always the threat of

the cops shutting down a concert, if the neighborhood mosque doesn’t

complain first. Time will tell if Microphone, padded with protest

songs, is a snapshot of pre-2011 Egypt or a momentary stand for the

freedom of expression. And where else are you going to see the

seven-year-old T, the youngest MC in Egypt?

For those who like their storylines streamlined, Mohamed Diab takes on

sexual harassment and internalized misogyny in the crowd pleasing and

polemical 678, inspired by real events. Storylines involving three women from different social/economic strata

weave in and out of each other—some coincidences click, some clunk. A

full-fledged two hander, 678 at times verges on turning into a

boo-hiss melodrama, but it’s the rare film that will elicit cheers

within the usually sedate Museum of Modern Art. Maybe now, thanks to

current events, the equally didactic but more diverting and

ambitious

Scheherazade, Tell Me a Story will finally receive the attention

it deserves. (A couple in Microphone even discusses this 2009

homegrown hit.)

Set in Ghana, American director Deron Albright’s The Destiny of

Lesser Animals bears the telltale signs of a first film—uneven

acting and simple camera blocking—but it has plenty of grit: stakeouts,

a woman of mystery, and the on-location hustle and bustle of the capital city,

Accra. A police inspector wants to return to the U.S., from where he was

deported years earlier. After saving up, he buys an expertly made

counterfeit passport—which is snatched from his hands immediately after

purchase. He then concocts a lie that his gun was stolen in order to

enlist the aid of a veteran cop to track down the culprit. Despite

obvious plot developments, the film takes a clear-headed and moving turn in tone

towards the end.

More an impressionistic photo-essay than documentary, El Velador

loosely follows the title’s night watchman, his dogs, and the

assembly-line construction of an ever-growing cemetery in northwestern

Mexico.

From one angle, a row of mausoleums (some sleek, some traditional, one

with an ornate chandelier) looks like a land-locked beach community,

except for the crosses everywhere. (El velador lives in the shack in the

background.)

News snippets from radio and TV of the escalating drug-related violence

provide the slenderest context about this boom town

for the departed. As the press notes state, it’s a film about violence

without violence. The film already has a date on PBS’s

POV series for 2012. How it holds up on the home screen (and any

nearby distractions) is another matter. On the wide screen, it’s easier

to surrender to the slow pace and the contemplative and

often peaceful ambiance. There the beautifully photographed film can be seen

to its best advantage.

Two young women, standing a foot apart, lean towards each other, tongues

squirming out, touching, and then slithering into the other’s mouth: a

hands-on tutorial between two friends. That’s the opening provocation in

Athina Rachel Tsangari’s

Attenberg, whose title derives from the name of natural history filmmaker Sir David Attenborough. Like Attenborough,

Marina (Ariane Labed) observes, taking an anthropological view of life,

especially when it comes to men. Humans are the animals on display here. But

like last year’s outsider entry, Dogtooth, also

from Greece,

Attenberg keeps the viewer at bay, deliberately trying to raise

eyebrows—Marina asks her father if he has ever imagined her naked; some

things should remain taboo, his reply. He’s dying of cancer and wants

his 23-year-old daughter to live outside her odd, insular bubble, and

Marina begins taking tentative steps, clinically approaching her first

sexual experience. (In exasperation, her partner/specimen pleads, “I beg

you, stop describing what you’re doing.”) Maybe after Dogtooth’s

transgressions, it’s a little harder to surprise us with eccentric

behavior. Kent Turner

Many of the films in the series look at young folks around the world

dealing with strictures on their lives. Of films not yet slated for

wider distribution, here are many that reveal young lives, from the most

constricted to those with too much freedom.

Curling

Twelve-year-old Julyvonne (Philomène Bilodeau) is kept in protective

isolation by her excessively fearful father, Jean-François (Emmanuel

Bilodeau). Surrounded by the limitless horizon of windswept snow in

rural Québec, her personal landscape is so undifferentiated that it’s a

surprise to both of them that she needs glasses. (They’re

sympathetically portrayed by a real-life father and daughter.)

Writer/director Denis Côté, in his fifth feature film, doles out some

hints and shocking glimpses of why the father goes to such extreme and

yet unsuccessful measures to keep her isolated. Through mostly silent

experiences, Julyvonne, more than a bit bizarrely, adapts to his

restrictions, such that joining with other families tobogganing becomes

a celebration of liberation for both of them.

Winter Vacation

There’s no shortage of comedies about holidays, spring breaks, and

summer vacations, but writer/director Hongqi Li’s third feature provides

a kids’ view of the frustrating limits during a week off from school in

China’s Inner Mongolia. The temporary break leaves nine bored teenagers,

two restless children, and their extended families and neighbors at

loose ends. They devolve into repetitive, and increasingly amusing,

routines. The deadpan humor is as dry as the snowflakes that cover their

bleak section of town dominated by drab, Soviet-era apartment blocks. No

wonder the little kids think that running away to be orphans would be

their best hope for the future than going as stir crazy like

the grown-ups.

Majority

In his first feature, writer/director Seren Yüce doesn’t seem very

optimistic about the young generation in Turkey raised with the material

benefits of corrupt crony capitalism. Since childhood, pudgy 21-year-old

college dropout Mertkan (Barta Kucukcaglayan) is bullied by his father,

who looks and talks a lot like a Turkish Tony Soprano gone just barely

legit in a booming construction business. Mertkan hangs out in Istanbul

with his dissolute friends, who sponge off him. His secret, though oddly

desultory, affair with Gül (Esme Madra), a Kurdish student/waitress from

a distant village, sparks a rebellious interlude before he’ll fall into

line in the army and the family firm. (In the English subtitles,

Mertkan’s friends and relatives pejoratively call her a “gypsy.”) In an

equally pessimistic view of women’s lot, Gül’s home life, which she’s

escaping from, must be pretty bad that being with the insensitive

Mertkan in the big city is an improvement.

Man Without a Cell Phone

Debut director/co-writer Sameh Zoabi returned to his home town of Iksal,

an Arab-Israeli village near Nazareth, to find unusually gentle humor in

the ironies and stresses of growing up modern in a traditional

Palestinian society surrounded by politics. A handsome 20-something

Muslim, Jawdat (Razi Shawahdeh), is stuck making concrete with his

cousin, unless he can pass the local university’s Hebrew exam. He would

keep juggling several beautiful women via cell phone—one with

disapproving Christian parents; another on the West Bank, inaccessible

through roadblocks and phone taps; and a college student, whose honor is

zealously guarded by her brother the policeman—if only Jawdat’s

suspicious father would stop messing with the cell phone tower on the

adjacent property. Entertainingly, Jawdat finds amusing ways to appeal

to everyone’s self-interest in organizing a protest against the Israeli

and local authorities to move the tower, and incidentally proves

that a flirt turned non-violent leader looks like a fighter, at least in

this breezy comedy.

Belle Epine

The good girl attracted to the guy racing motorcycles is a trope of

adolescent rebellion going back to The Wild One (1953). Debut

director/co-writer Rebecca Zlotowski delves unusually deep and

sensitively into what drives one French 17 year old to hop on back. The

family of Prudence Friedmann (Léa Seydoux) is reeling from the death of

the mother, making Prudence feel abandoned and alone, despite relatives

who take her into their observant Jewish home. She isn’t just led astray

by the bad girl at school. She chooses the dark thrills and excitement

of a late-night motorcycle hangout to mask her grief by experimenting

with sex and drugs until she can finally, and touchingly, face her

mother’s memory.

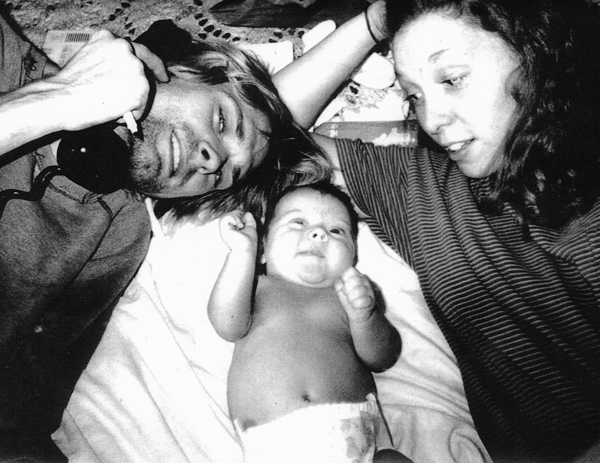

Hit So Hard

is a cautionary story of youth with too much freedom, with some new

angles to the usual Behind the Music arc of the rise, fall, and

difficult recovery of a rock star. Subtitled “The Life and Near-Death

Story of Drummer Patty Schemel,” director P. David Ebersole’s first

feature-length documentary is noteworthy for the intimate excerpts from 40-plus hours of hi-8 video footage Schemel took while recording and

touring with the Courtney Love-fronted band Hole in the 1990s, and (in

heartbreakingly happier times) living with Love, her late husband Kurt

Cobain, and their baby, Frances. In addition, Schemel’s brother—and

co-dependent addict—Larry saved tapes of all of her TV appearances

during the reign of Seattle rock. Highlighted by frank interviews with

her bandmates and music colleagues (particularly a starkly fresh

interview with the ever unapologetic Love), the film insightfully

emphasizes the difficulties of being gay first in a small blue-collar

town and then in a straight girl band, even while grunge adopted

lesbians’ flannel shirt style. Nora Lee Mandel

Hospitalité

Koji Fukada’s Hospitalité capitalizes on Japan’s insularity,

social rigors, and cramped living spaces to orchestrate a nuanced and

surprisingly insightful comedic gem. When a strange man weasels himself

into the quiet lives of a family living above their small printing

factory, he launches a campaign of charm and blackmail to turn their

lives topsy-turvy. Before long, marriage bonds are shaken and a conga

line of eclectic foreigners sends the xenophobic neighborhood into a

tailspin. The film swiftly moves from a simple narrative into an

absurdist, almost theatrical play, all in the confines of a small home

in downtown Tokyo. Hospitalité is as unusual as it is enjoyable.

Outbound

Another troubled voice from the Romanian New Wave follows a young woman

on 24-hour leave from a long prison sentence. Her intentions to flee the

country become clear after the first few scenes, but the rest of the

setup—who she is, what she’s done—are slowly revealed over the next 90

minutes. The camera often lurks behind as she walks with stoic

determination, visiting her estranged brother, her family home, her

degenerate ex-boyfriend, all in a mysterious effort to set the stage for

her escape. Bogdan George Apetri’s filmmaking is confident and

straightforward—no touching music or tempting flashbacks luring the

audience to commiserate. And though we may not grow to love her, her

tragedy is invariably felt.

|

Copacabana

In may be her most straight-laced role to date, Isabella Huppert plays Babou, a reckless, itinerant free spirit who has never grown up.

Outfitted in brightly colored miniskirts, saris, and furs, Huppert stars

opposite her real-life and on-screen daughter (Lolita Chammah) in Marc

Fitoussi’s charming family study. Her daughter revolts against a

lifetime of Babou’s unconventional ways by choosing to marry a safe

marketing executive (and not extending a wedding invitation to her

unpredictable and often embarrassing mother). In an attempt to change,

Babou then takes a job selling timeshares in Ostend, Belgium—possibly

the most depressing setting ever committed to screen. Despite the

predictable plot of this gentle comedy, the effect of watching it is a

pleasant one.

Memory Lane

Except for the occasional appearance of the Paris skyline, watch Mikhaël

Hers’s Memory Lane on mute and it’s almost indistinguishable from

a homegrown mumblecore indie. The sweet but sophomoric film is framed by

nostalgic narration in the style of a poem unabashedly read aloud in

high school French class. It’s the story of seven friends lingering

somewhere in their 20s, who reunite in their suburban hometown one

memorable August. Some come home under tragic circumstances, and others

have never left. In either case, the underlying emotions are dulled by

the fitting marriage of sexy French insouciance and indie cool—so much

so that it takes the length of the film to become emotionally involved

with even the fieriest of characters.

Some Days are Better Than Others

Carrie Brownstein should stick to

promoting Portland in her own ingenious sketch comedy show Portlandia

because this feature film take on the city (in which she stars) is a

bland, uninspired flop. Joined by James Mercer (lead singer/songwriter

of the Shins and Broken Bells, and a dead-ringer for a young Kevin

Spacey), this uber-talented indie duo can’t save director Matt

McCormick’s cookie-cutter exploration of awkward and aimless young

adulthood. As so often happens, there is a bevy of painfully sincere

characters desperately trying to communicate. Except for Mercer’s

somewhat charming karaoke of “Total Eclipse of the Heart,” the film

makes no overtures to the cast’s musical talents. (Brownstein is also

the former guitarist/vocalist for the Portland band Sleater-Kinney). And

except for some shout-outs to Stumptown, community gardens, and swaths

of unemployed quasi-youths, Some Days are Better Than Others

could have been set in any other city where, according to independent

cinema, boredom and shyness reign supreme.

Summer of Goliath

Summer of Goliath

is a desperately arty portrayal of a Mexican village composed of several

disjointed character portraits. An odd combination of documentary and

fiction, the film centers on a woman spiraling out of control after

being abandoned by her husband, two teenage soldiers itching to be

issued machine guns, and a spattering of peripheral town folk rounding

out the narrative mess. The film’s yearning for artistic credibility is

rewarded in some beautiful out-of-focus shots, but other excessively

long and tedious scenes reek of self-indulgence. Director Nicolás Pereda touches

on a torrent of issues—corruption, violence, poverty—and makes the audience

dizzy with all of these unexplored scenarios, but the result is

ultimately a failure.

Gromozeka

This

is the result of a strained and misguided attempt to add meaning and

symbolism to the melodramatic filmmaking for which Russian filmmakers are known.

This devastating (and not in a good way) story of three middle-aged men

carving out a sad existence in a gloomy wintry Moscow is so ludicrously

stuffed with sins and calamities it’s difficult to decide who we’re

supposed to feel sorry for. As if unable to pick just one tragic twist

from a screenwriting brainstorm, director Vladimir Kott eagerly delivers

illness, prostitution, violence, and more than one marital breakdown to

his supposedly tear-starved audience. What’s worse, potentially

beautiful scenes staged to deliver optimal poetic meaning (an

optometrist speaking to her estranged husband through her optical

refractor) are delivered so often and so shamelessly, the entire film

quickly begins to feel like a joke.

Tyrannosaur

On a different note, here’s

a film to look out for. Actor-turned-director Paddy Considine’s festival

standout Tyrannosaur is a frightening depiction of socialized

violence in an English backwater. Peter Mullan commands the screen as

Joseph, a mean, lonely, old drunk whose violent temper constantly

overflows into bloody altercations. His performance is as loud and

turbulent as it is achingly tender. When Joseph’s life become

intertwined with a local woman, whose lot may be more desperate than his

own, he tries to see himself through her pious and forgiving eyes to

decide whether or not he is, in fact, a monster. The violence on the

screen is degenerate, believable, and deeply frightening. A heinous

perpetrator one moment, Joseph becomes an innocent victim the next,

an unexpected nuance in a film which, in less talented hands, could have

been left the characters in black and white. It’s due for release this fall. Yana

Litovsky

March 25, 2011

Home

About

Film-Forward.com Archive of Previous

Reviews

Contact

us

|