|

Reviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

The 20th Annual Human Rights Watch International Film

Festival The power of film to shed light on the tragic path from bigotry to genocide is reflected in the International Film Festival, organized annually by Human Rights Watch in New York City and London before touring the world. The most nuanced and engrossing film previewed is My Neighbor, My Killer on the aftermath of Rwanda’s 1994 genocide that brutally wiped out three-quarters of the Tutsi population. Director Anne Aghion culminates a decade-long commitment to follow the implementation of what is literally a grassroots approach to justice, called gacaca, which means “justice on the grass” in Kinyarwanda. She will receive the Nestor Almendros Award for courage in filmmaking at the festival. The discovery of yet another enormous mass grave in the opening scene emphasizes how fresh the emotional wounds remain. Regional General Prosecutor Jean-Marie Mbarushimana then explains to crammed prison cells of Hutu génocidaires that they will be released—to face tribunals of their neighbors in their home towns. The director follows two perpetrators home to rural Gafumba, almost three hours from the capital of Kigali, and the reactions of two women survivors dreading their return, both Hutu widows of Tutsi husbands and mothers of murdered children. Over three years of weekly testimony, the entire community comes out on the grass (like a New England town meeting on the commons) to point out in vivid detail what exactly happened where. When the defendants try to use vague language or excuses, their neighbors quickly correct their evasions: how could it be mistaken identity when you were the victim’s brother-in-law? How could your armed patrols be justified when we lived together in peace and the victims had no weapons? Away from the formal procedures, amidst the lush agricultural landscape and the grind of daily chores, Aghion gained an extraordinary level of intimacy and trust to elicit participants’ feelings about the past and the future. (One widow turns to her friend: “They ask us if we are happy! These whites ask the strangest questions.”) The quiet reality is even more moving than how fiction grappled with this unique judicial process in Raoul Peck‘s Sometimes in April and Lee Isaac Chung’s Munyurangabo.

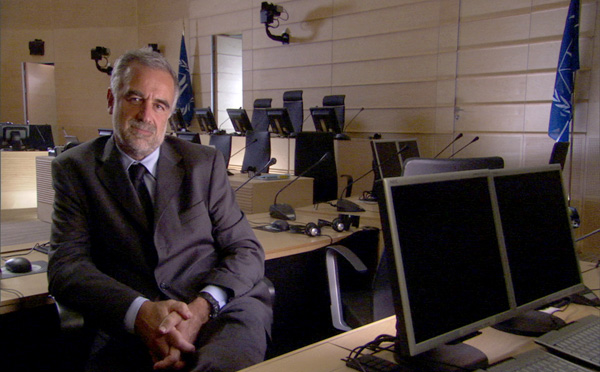

In 2005’s State of Fear, Yates used the findings of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission as background for a straightforward history of terrorism and repression, but this film feels more like a commissioned, official report. She covers the founding of the ICC in 2002 as the first permanent tribunal set up to prosecute individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. Yates tracks how it picked its first battles to establish credibility and authority where a country’s justice system fails, even without the participation of China, Russia, India, and the United States. Over three years, across four continents, Yates extensively interviewed the court’s hard-working, peripatetic staff as they travel from The Hague to Colombia, Somalia, Uganda, the Congo, and the United Nations. It is high drama when charismatic chief prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo is seen challenging the U.N. Security Council that diplomacy as usual is a cover-up of genocide in Darfur. For much of the film, the only critics of the court interviewed are war lords or right-wing ideologues. Michael Christoffersen’s Milosevic on Trial (2007) was a much more considered and thoughtful look at the strengths and limitations of the adversarial courtroom format for trying lying, conniving, flag-waving nationalist mass murderers, until The Reckoning travels to Uganda, where villagers and refugees speak up to challenge the court’s methods in dealing with the Lord’s Resistance Army leaders. While these fighters may be among history’s most reprehensible, the issue of justice as being culturally defined is eloquently and emotionally debated among non-lawyers who have lived with horrific violence and its consequences. However, minimal identification of some of the speakers confuses their varied opinions. The Reckoning will be broadcast in the U.S. on PBS next month as part of the POV series. Genocide haunts Look Into My Eyes, Naftaly Gliksberg’s documentary on anti-Semitism. In a fraternal rivalry-like coincidence, anti-Semitism is also the subject of Yoav Shamir’s Defamation, which premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival and will be released by First Run Features this fall. Both Israeli films go around the world to gauge bias against Jews. They even visit some of the same locations in Brooklyn, Eastern and Western Europe, and the former Soviet Union. While both filmmakers are descendants of Holocaust survivors, Shamir is secular, and identifies himself as part of a majority. In examining recent incidents, he is most effective at questioning the institutionalization of anti-anti-Semitism. The older Gliksberg was raised Orthodox, has lived as a minority outside Israel, parses attitudes, and most effectively points out the power of stereotypes. Shamir is more iconoclastic and skeptical, Gliksberg more conventional and confrontational, but both use genial humor to draw out revealing interviews. They mostly come to opposite conclusions about the endurance of anti-Semitism, the impact of Holocaust awareness, and Israeli-Palestinian relations on threats against Jews internationally. Viewers can make up their own minds by seeing both films. Several

other buzzed about films in the festival already have commitments for

television or theatrical releases later this year.

Havana

Marking’s

Afghan Star

will be released by Zeitgeist Films later this month.

Andy Bichlbaum and Mike Bonanno’s sequel,

The Yes Men Fix the World,

premieres on HBO in July, and

Joe Berlinger’s

Crude will be released by

First Run Features in September.

Nora Lee Mandel

|