|

Reviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

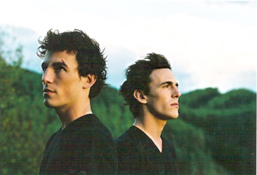

Directed by Pascal-Alex Vincent Produced by Nicolas Brevière Written by Vincent, Martin Drouot & Olivier Nicklaus Released by Strand Releasing French with English subtitles France. 77 min. Not Rated With Alexandre Carril, Victor Carril, Anaïs Demoustier, Maya Borker & Samir Harrag

The first five minutes of Give Me Your Hand are, in short, really, really cool. Two nameless young brothers leave their father’s bakery on a quiet, starry night. One sprints across the train tracks, skirting death by a hair. The other waits for the train to pass, and then jumps his brother in the grass. They fight, and it’s unclear whether the fraternal tussling is serious or play. Introduction, relationship, and conflict all elegantly set up under 10 minutes and without the aid of dialogue. And the cool factor—the entire sequence is animated, adding a fantastical edge to the every day. It’s like a modern day Grimm’s fairy tale. But then we fade into reality (or a standard cinematic film), and we watch what seems like an endless montage of the brothers traveling. They are Antoine (Alexandre Carril) and Quentin (Victor Carril), backpacking to their mother’s funeral in Spain, a mother they did not know and do not remember. Quentin, the artsy one, constantly draws cartoons in a notepad he carries around. Antoine is the social, extroverted one, prone to action and braggadocio. Despite these differences, it is hard to tell where one brother leaves off and the other begins (no doubt aided by the fact that the Carrils are identical twins). With features that look like they’re carved from granite, with curly, wayward black hair, and basic T-shirt, jeans, and sweatshirt ensembles, you can trade one for the other. When Antoine tells a young woman of Quentin’s pictures, “We drew them,” you feel even the brothers have problems maintaining separate personas. Then Quentin snatches the art away. Antoine’s lie creates a fissure in the rock of their shared identity that will soon crack and split into two. On one level, we have a road trip film; on another, a coming of age story. The third, and strongest, is that of brotherhood. The story of Antoine and Quentin is like that of Cain and Abel, or Romulus and Remus. Director and co-screenwriter Pascal-Alex Vincent’s mostly dialogue free film relies heavily on images to extrapolate from the personal relationship between the brothers to a more general metaphor. One of the movie’s most arresting is that of the two brothers, curled up asleep in a large metal tube, looking for all the world like two babes sharing a womb. That peaceful picture is slowly and inevitably shattered, with each change triggered by their desire, or love, of other people. It culminates when Quentin enters into a homosexual liaison that Antoine cannot understand. The latter, bewildered and hurt, reacts by betraying his brother by selling him to a stranger in a bathroom. The betrayal marks the definite separation of the brothers, both spiritually and in the film. The performances of the Carrils are restrained, their characters revealed through the tightening of a jaw or the upturn of a sulky mouth. They are never quite fully fleshed out, which may be a directorial choice. If Quentin and Antoine are to be archetypal figures, neither can contain the quirks or eccentricities that turn qualities into personalities. The other actors, too, are subdued. The ones that do manage to register are Anaïs Demoustier, as a troubled, free-spirited gas station worker, and Maya Borker, as a lonely woman in the woods. Loneliness

permeates the film, emphasized by close-ups that never seem to reveal

exactly what the characters are thinking. People connect, but ever so

briefly. For the director, no person can ever know another, no matter how

close they are or the shared DNA. That separation is painful, even

homicidal. Even brotherhood cannot overcome the breach, and the last

image, of one brother walking away from another, has a finality that

scorches the viewer.

Lisa Bernier

|