Reviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

Directed by Julian Schnabel. Produced by Kathleen Kennedy & Jon Kilik. Written by Ronald Harwood, based on the book Le Scaphandre et le Papillon by Jean-Dominique Bauby. Director of photography, Janusz Kaminski. Edited by Juliette Welfling. Music by Paul Cantelon. Released by Miramax Films. France/USA. 112 min. Rated PG-13. With Mathieu Amalric, Emmanuelle Seigner, Marie-Josée Croze, Anne Consigny, Patrick Chesnais, Niels Arestrup, Olatz Lopez Garmendia, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Marina Hands, Issach de Bankole & Max von Sydow.

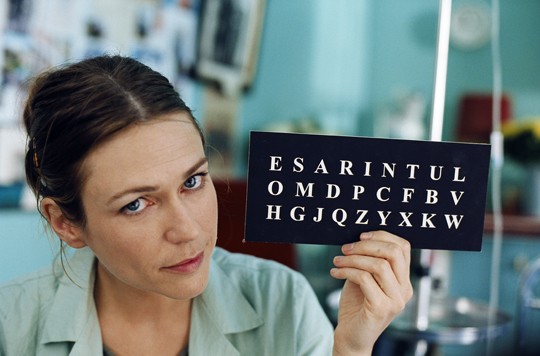

Screenwriter Ronald Harwood solves the problem of how to dramatize the book’s inner monologues by having Jean-Do speak, though only in voiceover, and Schnabel tells much of the story from Jean-Do’s point of view: when he wakes, after three weeks in a coma, the footage is overexposed and blurry. The film, though, leaves behind the confines of his seaside hospital and runs rampant down memory lane of girlfriends past and present, including one homage/send-up of From Here to Eternity’s beach scene. His imagination, and Kaminski’s camera, roams to the Alps and Martinique, and much of what we see is how Jean-Do wishes to be seen, as a downhill skier or the physical embodiment of Marlon Brando, circa 1951. The movies-within-the-movie device originated in the book, where Jean-Do declared, “I am the greatest [film] director of all time,” picturing the view from the hospital terrace as a film set in a chapter called “Cinecettà.” (In keeping with the life-as-a-movie theme, all of the women are lookers.) Harwood’s voiceover echoes the book’s self-deprecating sense of humor and much of its observations. However, unlike in the memoir, Jean-Do can swivel his head, and he’s married. But Harwood ups the tension by providing a distant girlfriend and a devoted ex, Céline (Emmanuelle Seigner), the mother of his two children.

Meanwhile, Schnabel has it both ways. He recognizes the impulse to give into pathos, which, given the circumstances, would be impossible to avoid, but

he also resists sentimentality. Instead, he knows that it is more moving to see a character struggle for composure and, more often than not, fail. In

doing so, Schnabel gets perhaps the most vulnerable performance from Max von Sydow, as Jean-Do’s leonine 92-year-old father. And often cast as a cold,

impenetrable goddess, Seigner’s hardness has recently softened, like her maternal whore in La Vie en Rose. Here, the ice completely

melts – she’s a revelation.

Kent Turner

|