Reviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

Directed by: Jeff Feuerzeig. Produced by: Henry S. Rosenthal. Director of Photography: Fortunato Procopio. Edited by: Tyler Hubby. Music by: Daniel Johnston. Released by: Sony Pictures Classics. Country of Origin: USA. 110 min. Rated: PG-13. DVD Features: Director & producer commentary. Deleted scenes. Sundance world premiere featurette. Laurie & Daniel reunion featurette. Legendary WFMU broadcast featurette. Cinema of Daniel Johnston (three short films). Daniel’s audio diaries. French subtitles.

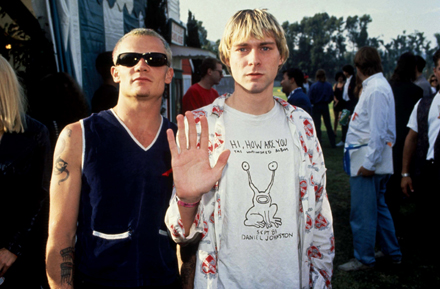

A gifted and self-taught musician and filmmaker, Johnston’s imaginative S-8 home movies and his melodic songs of teenage alienation (“The artist walks alone…”) made him an “art star” in his high school in Virginia. But his mother Mabel knew Daniel was different from early childhood. Conservative Christian fundamentalists, his parents could be stand-ins for an entire generation bewildered by the late-20th century generational and cultural gap. In a family fight Johnston tape recorded, his mother calls her youngest child, “an unprofitable servant of the Lord,” fearing his pursuits would lead to a self-absorbed life. Whatever judgments a viewer may have regarding his family will be challenged by the film’s end. Reticent and forthcoming, his plainspoken father and almost the entire Johnston family movingly come clean before director Feuerzeig’s camera. Although Daniel would attend Church of Christ services, he only went to check out the girls. What’s not mentioned in the film is the irony that musical instruments are not accepted as part of the worship service. Hymns are sung a cappella. The one belief of the church that did firmly take hold in Daniel: Satan as a literal being. After a mental breakdown during his first year in college, Johnston drops out and suddenly disappears. While his mother thinks he could be in a shallow grave, he joins a carnival, quitting it when it arrives in Austin, TX, just at the moment its alternative music scene is about to take off. His stream-of-conscious music, accompanied by his cracking, nasally vocals and spacey stage presence, finds a cult following. Like Petrarch, Johnston’s pines for a Laura in his music – a college crush named Laurie Allen. And in 1986, he wins local awards for best songwriter and folk artist, even though he really didn’t know how to play guitar. What follows is unlikely stardom on MTV’s The Cutting Edge. But a hit of acid at a Butthole Surfers concert, further drug use, and a magnified obsession with the devil lead to one of many hospitalizations; 1987 proves to be just one of his lost years. Without question, Johnston plays to the camera, any camera, whether in the contemporary interviews or the abundant home-made footage. But in his own way, he’s a natural showman, with or without medication, who has been documenting himself his entire life. (Although I could have done without Johnston, now in his forties, decked out as Casper during the closing credits). In one audio recording, he mockingly acknowledges, “I’m a manic depressive with delusions of grandeur.” The arguments against Errol Morris’ use of reenactments or the slo-mo flying milk shake in The Thin Blue Line now seem quaint. As Johnston hits the road across America and comes back to his aging parents’ home, so does Feuerzeig. His reenactments, filmed from Johnston’s point of view, and roving camera visually enhance the interviews of friends and family. Fortunately for the director, it seems like all of Johnston’s life has been caught on camera, including his proselytizing a jaded New York crowd during a relapse when he went off his meds. Thanks to Woody Allen, clips from Broadway Danny Rose provide an affectionate tribute to Johnston’s loyal and tenacious manager, Jeff Tartakov.

Johnston’s story may seem like another ‘80s cultural footnote, but just when you think it’s over and you’ve seen it all, another fascinating chapter in his eventful life comes along. Serendipity plays a key role here. The film more than lives up to the sentiment of Austin musician Kathy McCarty, “In terms of creating a legend, [Daniel]’s done everything right.” Feuerzeig paints both an in-depth look at Johnston and at an era, giving more resonance than the bulk of recent musical bio-docs (Be Here to Love Me and the bittersweet New York Doll).

DVD Extras: Like in the film, the best of the bonus materials focuses on Johnston and his family, particularly his parents. The most fascinating deleted sequence is a trip to South Africa, where Johnston was to supervise the tribal music in Peter Jackson’s remake of King Kong. The segment concludes with a scene from Daniel’s fantasy world: he’s dressed in a monkey suit, perched on a ladder with a Barbie-looking doll in his paw, while his dad, in an aviator’s cap, circles around him with a toy plane attacking Kong, reenacting the big ape’s death scene. (I don’t know if you can read deeper meaning into this role-play, but I don’t know too many dads who would play along with their forty-something son in this manner.) Among the audio diaries, there are two excerpts that Johnston's mother probably wishes he hadn’t recorded, (#7 & #12), both taped during an argument. In the latter, she tells him, “You’re no friend of mine Danny Johnston, you’re my enemy,” for making a fool of her in front of his friends. The other audio segment, the “Legendary WFMU Broadcast,” begins with an announcement made by Johnston (who plays all of the program’s characters) that New York has been invaded by Casper the Friendly Ghost. The segment also includes a disconcerting tirade against the fictional music manager, Jiffy Tartar Sauce, who admits, “Because I am a Jew. I like money a lot.” Again, his mom is the butt of his jokes: “My mother is so old, she’s not just a mother, she’s an ancestor.” However, in the featurette covering the film’s Sundance world premiere, he praises his mom and dad for being great parents to him all of his life. (Incidentally at the festival, he meets fan John C. Reilly.)

Feuerzeig has more than succeeded in exhuming a footnote, though it’s another question if the viewer will agree with his commentary's

description of Johnston as “a major note in art history and music history.” He also acknowledges his luck in covering “the most

documented family on earth.” Besides Johnston’s self-made films and video/audio recordings, his father has been a lifelong amateur

photographer. The director does admit, though, that the West Virginian mental hospital was not as decrepit when Daniel was treated

there as it appears in the film. The institution has since been closed after a scandal, though Feuerzeig’s footage of darkened hallways with wilted and crumbling plaster does give the film a Dickensian tone.

Kent Turner

|