|

Reviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

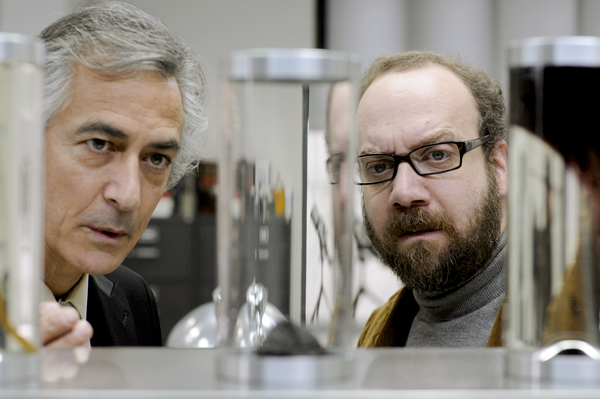

COLD SOULS In a moment of existential dread, Uncle Vanya confesses, “I could have been a Schopenhauer…a Dostoevsky!” At the time, the line from Chekhov’s play, regarding Vanya’s wasted potential, reflected a prevailing cultural neurosis. Newcomer Sophie Barthes has gone farther in framing this desperation. Paul Giamatti plays himself playing Vanya in a new Broadway production, and it’s all three of these men who seem to deliver the line, and if that’s not meta enough for you yet, Mr. Giamatti also happens to be a founding partner of Touchy Feely Films, who, along with Journeyman Pictures (Maria Full of Grace, Half Nelson), produced Cold Souls. The film may not be perfect, but there’s certainly not a lot of wasted potential to be found here. For a debut, Ms. Barthes’ heady tragicomedy is considerably accomplished, offering hilarious quirks and presenting a fine glimpse into the complexities of the human experience. All this while skillfully steering away from what could have easily been the Paul Giamatti Show. A superstar in his own right—at least to the more film literate of today’s audiences—Mr. Giamatti is an unquestionably magnetic presence, and nobody does angsty self-doubt like he does. Barthes has said she wrote the part with the actor in mind, but she actually wrote the actor into the screenplay. With all the layers of reflexivity at work here, it’s sometimes difficult to discern Giamatti the actor from Giamatti the character. Though for all its humor (watch for David Strathairn’s brilliant Dr. Flintstein, in particular), a somber mood persists throughout. It’s Being John Malkovich all over again for a slightly stuffier crowd. Feeling mired in Chekhov’s hopeless pessimism, Paul undergoes an experimental procedure whereby his soul is physically removed from his body and placed in a storage unit. Without the burden of his soul, he’s noticeably less affected by life’s drama, but without its guidance, his work on Uncle Vanya is in jeopardy. Renting the soul of a Russian poet so that he might continue his role, Paul is exposed to the seedy underbelly of international soul trafficking. It’s here that Ms. Barthes’ film takes an interesting turn. Eventually, the parallel stories converge, but for much of the film we’re witness to the daily work of Nina (Dina Korzun) the “soul mule,” a Russian woman tasked with transporting hundreds of souls to the United States, away from their original donors—working-class Russians for whom the small fee is worth trading the burden of a thoughtful existence. She weekly transports so many souls that the residues actually begin to accumulate in her body. The immediately familiar story recalls such modern-day horrors like sweatshop labor and human trafficking, and Ms. Barthes clearly revels in her pertinent cultural references, missing no opportunity to drop a buzz term here or there. Without ever taking a political stance, references to marketplace regulation, hedge funds, and the Department of Homeland Security are all thrown into the mix. Barthes is perhaps astute enough to recognize the pieces that compose modern capitalism, but she disallows any clear thesis or critique to develop. This is also a problem with the philosophical ramifications of the film. The way a soul feels, unfortunately, does not play well on screen. Barthes and Giamatti are obviously on a similar wavelength, and changes in Paul’s demeanor are apparent, but the only definitive point made about the human soul is that it allows one to be a better actor. Even when Paul chooses the Russian poet’s soul over his own, the outward effects are almost identical. During the dream sequences, a glimpse inside the souls themselves, we see nothing more than stockpiles of powerful imagery. Rather than

running circles around the sketchy philosophy, a better way to approach

this film is to appreciate the more immediate story being told. Nina suffers greatly from the burden of all the trafficking,

yet it’s almost as if her conscience is weighing more heavily on her

than the ostensible “soul residues.” She’s a part of the exploitation

process, selling premium souls to rich Americans. Sophie Barthes’

seeming insinuation—that our conscience is actually a big part of what

we call a soul—is, for my money, a pretty satisfying point to make.

Michael Lee

|