Alex Gibney models his critical analysis of the veneration of Steve Jobs on Citizen Kane by opening his documentary with the innovator’s death at the age of 56 in 2011. Over TV news clips of virtual candles on iPhones and other Apple devices held up in front of Apple stores around the world, Gibney begins narrating a more philosophical than investigative search behind the official story of “Citizen Jobs.”

Made without the cooperation of Apple Inc., Jobs’s family, and the many people Gibney would have liked to interview, the first half is primarily biographical, with a lot of well-researched photographs and archival footage and sit-downs with those who were a part of Jobs’s personal and professional lives. Noticeably, some say almost word-for-word what was quoted in Walter Isaacson’s 2011 biography.

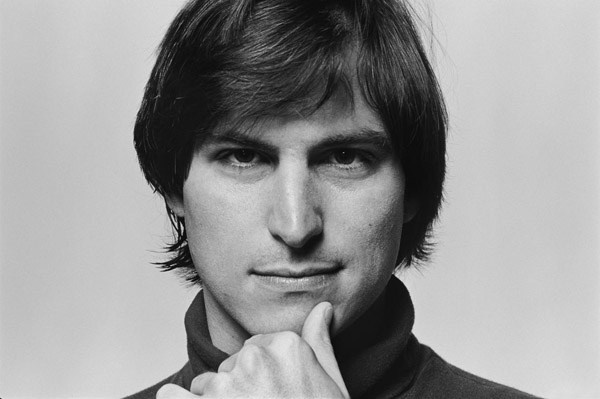

Gibney stylistically draws on his prolific experience profiling narcissistic control freaks obsessed with marketing themselves: Eliot Spitzer in Client 9 (2010), Julian Assange in We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks (2013), and Lance Armstrong in The Armstrong Lie (2013). In the Star Trek-influenced lingo of the emergent Silicon Valley, Jobs’s colleagues call the power of his one-on-one influence “a reality distortion field” that would motivate them to accomplish the impossible—symbolized here by repeated images of his unblinking stare-down. A barrage of talking heads, many who identify themselves as admirers (advertising executive Regis McKenna) and as still-smarting victims (friend/employee Daniel Kottke), recall his intensity.

The camera returns, like Jobs did, to the silent, meditative garden in Japan’s Eiheiji Buddhist temple, where his Zen master Kobun Chino Otogawa (seen in a rare archival interview) studied before leading centers in northern California that Jobs frequented. But just as Jobs and other counterculture acolytes looked East for peaceful spirituality, he also admired the country’s pioneering technology corporations, one of which once unleashed the marvel of the Walkman on the world. (Job triumphantly returned as Apple CEO in 1987 two years after his ouster, and Apple, the once start-up, turned more and more into a giant like Sony.)

Gibney accepts the usual “Rosebud” that Jobs was looking for a father figure because of his adoption, and several interviewees modestly take such credit, such as Atari co-founder Nolan Bushnell. (It’s not unlike Robert Altman’s Nashville where several women in an audience think Keith Carradine is singing “I’m Easy” directly to them.) But as an observer around the same age as Jobs and Gibney, I’m surprised the director misses a significant Silicon Valley narrative that permeates popular culture. It helps to explain the depth of grief at his passing.

While much is always made, as here, about Jobs meeting the youthful Steve Wozniak, his future Apple co-founder, through a Homestead (CA) High School friend, Isaacson’s biography points out that Jobs only attended there because he was being bullied at his original school in his family’s more working-class town. He insisted his parents find the funds to move to a more upscale neighborhood with better schools. Although people from work (such as Mac designer Bob Belleville) and his personal circle (particularly ex-girlfriend and mother of his first child, Chris-Ann Brennan) detail what a bully he could be to reach his impossible goals, there’s no reflection on the impact of this formative experience on his life.

This was brought home to me recently when my high school bullies and their supporters on my small hometown’s Facebook page still denied their aggressive behavior—via the Internet, tapping out “Get over it!” probably on an Apple device—completely oblivious to the irony of how they treated the nerds, geeks, or whatever “the smart kids” were called in your school, who were the types who developed Apple’s tech tools.

Jobs’s bullying is central to the criticisms and analysis that dominate the film’s second half, though most of the corporate charges are familiar, such as dangerous working conditions at Foxconn factories in China, Apple’s largest contractor, and accusations of Silicon Valley’s collusive hiring practices. Writers for the “Gizmodo” blog describe the storm trooper tactics Jobs used against them when they accidentally found a prototype iPhone (with shades of control techniques Gibney documented in Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief earlier this year). Jobs gets to extensively defend his management and business practices through a videotape of a 2008 deposition at the Securities and Exchange Commission, in the face of glaring evidence of back-dated stock options for himself and select employees.

Journalists Peter Elkind, who also collaborated with Gibney on the Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005), and Joe Nocera recount how Jobs’s courtship for good coverage later turned to vindictive fury at negative reports on his increasingly gaunt physical appearance while he was still denying health problems. Photographs are startling proof of how much he changed over the years.

Gibney mocks Jobs’s constant vague reference to “values” by comparing Apple’s 1997 “think different” advertising campaign that used the likenesses of boomer counterculture icons to Apple’s mixed record on corporate donations (though it is not as chintzy as he claims). Certainly, Jobs lack of personal philanthropy is noteworthy compared to the impact other Internet billionaires were starting to have—Microsoft founders Bill Gates and Paul G. Allen, and eBay’s Jeff Skoll. Neither did Jobs deign to model himself on the likes of earlier ruthless entrepreneurs John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie in what they did with their fortunes.

Gibney marvels that the mourners all bought into the values Jobs promoted, along with his products, as his benevolent contribution: that what was good for Apple was good for the world and that he was its personification of its beautiful game-changing products. I was struck how much the man in the black turtleneck seemed like his generation’s Walt Disney, another entrepreneur who personified a corporation and a money-making magic kingdom. Ironically, the Walt Disney Company’s 2006 purchase of Jobs’s Pixar animation studio made him Walt’s successor as the largest stockholder and, in the public’s perception, visionary.

Leave A Comment