In the age of punditry dominating 24/7 cable TV news and Internet bloggers, tweeters, and infotainment gossip, it still matters that The New York Times, “The Great Gray Lady” founded as a counter to the 19th-century yellow journalism tabloid newspaper wars, seems to be one of the last, quaint bastions of standards of accuracy. However, A Fragile Trust: Plagiarism, Power and Jayson Blair at the New York Times shows that looking closely at journalism today makes it look like messy sausage making, similar to the legislative process the press criticizes.

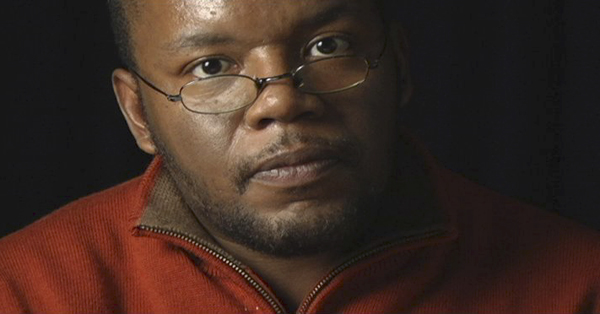

The opening montage of gleeful TV anchors in May 2003 pouncing on The Times’ published investigation of dozens of fraudulent articles written by Jayson Blair hones in on one repeated question posed to the accused and confessed reporter: Why? Director Samantha Grant conducts extensive interviews with Blair on the chronology of his shocking lack of professionalism, with explicit details about his manic depression and cocaine use, supplemented by audio excerpts from his self-serving 2004 memoir Burning Down My Masters’ House: My Life at the New York Times.

What becomes more eye-opening is how long he got away with erratic behavior, fictional travel, faked interviews with sources, and plagiarized quotes and descriptions, and how he got promoted to cover more and more prestigious assignments and front-page stories despite being just in his early twenties. Shouldn’t a cub reporter move up from regional newspapers, where a young journalist learns the ropes and gains practical experience?

After tracing how the liar was first exposed by a plagiarized journalist in such a local paper—ironically by a San Antonio reporter, Macarena Hernandez, who had a 1996 Times internship with Blair—three institutional factors are explored as fostering an enabling environment. First was the economic pressure pushing the paper towards digitization and the Internet. The goals of new executive editor Howell Raines and his caustic management style became a primary point of contention in most gossipy outside post-mortems of the scandal. The interviews with former and current Times writers and editors pile on the details of Blair’s ambitious sycophancy and name-dropping, all oddly combined with his erratic social skills and the complaints from supervisors about his lack of cogent explanations for the high number of corrections his pieces generated.

What is more startling is the lack of inter-departmental communication in a dysfunctional organization as he was moved around from beat to beat, let alone any action on the part of human resources. (Not clarified, though, is that there may have been legal issues involved when Blair entered employee rehab programs and hospitalizations.)

September 11, 2001 struck only days after Raines took over, and the staff was thrust into months of intense coverage that resulted in a record-breaking seven Pulitzer Prizes. The interviews well convey the stress the entire staff was under to produce investigations into the attacks and the poignant “Portraits in Grief” of the victims. Blair made a series of unsubstantiated claims to excuse himself from the coverage, and certainly the senior staff was distracted, and all hands were needed on deck for other news.

The third, most controversial, accusation was if Blair was hired, promoted, and continually excused because of his race (he is African American), due to The Times’ efforts to encourage diversity in a majority white newsroom. The anger of other African-American writers and editors about this accusation is palpable. They point to disgraced white reporters who weren’t identified as emblematic of race. (Or gender—no mention is made of Judith Miller, whose 2003 championing of the false weapons of mass destruction evidence in Iraq and reliance on duplicitous sources was a major embarrassment.)

The most clarity, though, comes from one of two outside journalists, Seth Mnookin, author of Hard News: Twenty-one Brutal Months at The New York Times and How They Changed the American Media. He provides insightful challenges to the insularity of The Times’ perspective, in which many writers shrug at such practices as “toe-touch datelines,” where reporters fly to an airport in order to file an already written report from the locale. He charts how Blair’s manipulations started at his high school newspaper.

Too much emphasis is put on the comparison with some mythical good old days that had higher standards of reporter honesty and editorial fact-checking in the self-styled newspaper of record. My first letter to The New York Times was in August, 1968, challenging the inaccuracy of their printing of a speech at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The transcript missed the notable spontaneous insertions—just like one of the (minor) charges against Blair when he didn’t actually attend an event at Madison Square Garden

There is only a brief interview with the public editor, an ombudsman position that was instituted after the scandal and has had uneven impact since. Or the noting that the biggest surprise many readers had from reading the four-page exposé on Blair was that one could challenge the accuracy of articles, and that the newspaper was keeping track of corrections for personnel reviews. Having worked for government and in public relations for non-profits, I used to just shrug at errors as par for the course. Now I turn to the corrections listings like reading a continuing saga in the newspaper that is as fallible as the people who write and edit the first draft of history.

Leave A Comment