A scene from part one of DREILEBEN (Photo: The Film Society of Lincoln Center)

For the last three years, the New York Film Festival has showcased international television mini-series that not only have creative and production values worthy of the big screen, but are not yet available on American television, even though media boundaries these days are so permeable. Dreileben will particularly appeal to fans of dark mysteries for the story, style, and structure of teasing clues and revelations across a trilogy of 90-minute chapters. A joint project of three German new wave directors, their film-school aesthetic theories are put into intriguing practice as each presents a different, jigsaw puzzle-like, complementary point of view of a crime—a convicted sex offender’s escape through a misty forest—and the uneasy impact on the men and women directly and indirectly involved in the police hunt. With the same characters shifting between foreground and background, each suspenseful installment is redolent with sirens, roadblocks, and threats, and no one is what they seem to be.

In Christian Petzold’s Part One: Beats Being Dead, a med student, Johannes (Jacob Matschenz) is so caught between heavy flirtations with a sexy, complicated Bosnian immigrant and his boss’s petulant daughter that he barely realizes he’s allowed the convict to escape from his hospital and that an investigation swirls around him while he moves back and forth between the two women. Part Two: Don’t Follow Me Around by Dominik Graf, the auteur least known to foreign audiences, brings in the familiar expert police profiler, Johanna (Jeanette Hain), to get inside the escapee’s head. She’s also involved in another triangle. In Part Three: One Minute of Darkness, an obsessed investigator is driven to his own health crisis by the case. But as Christoph Hochhäusler proved in his I Am Guilty (2005), the thrill is intimately following the disturbed criminal, though the sometimes limited English subtitles frustrate a key solution to his animalistic ramblings.

The festival goes from such realistic fiction to reveal behind-the-scenes reality in documentaries. Like much of the world, Italian documentarian Stefano Savona was glued to Al-Jazeera’s coverage of the January anti-government demonstrations in Egypt, but on the fifth day he took his camera to Cairo, a city he’d been visiting annually for years, and plunged into making Tahrir. He found three young, enthusiastic, articulate participants who are so cinematic they seem like the fictional symbols Haskell Wexler inserted into the similar immediacy of 1968 Chicago in Medium Cool. Their continuous political discussions about protest tactics and the future of their country start to sound like late night dorm bull sessions, but then older Egyptians arrive from outside the city to exult how this basic freedom of expression was denied them during the past three decades. The bloodied victims carried from the brutal attacks during “the day of the camels” add vivid urgency to their heated debates. Savona roams through different constituencies in the square, including the praying cadres of the Muslim Brotherhood, and his determined guides even lead him right onto the platform next to Internet activist Wael Ghonim, emotionally trying to stop the packed crowd from acclaiming him a hero after his release from jail. While Savona’s experiential approach could use more informational inserts and context, this exhilarating documentary captures the heart of the tumultuous weeks that changed Egypt, the Mideast, and maybe the world.

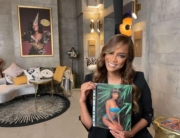

George Harrison (Photo: The Film Society of Lincoln Center)

The first half of Martin Scorsese’s two-and-half-hour documentary George Harrison: Living in The Material World gives the inside scoop on the lead guitarist of the phenomenon that was the Beatles. Brief interviews with Harrison’s siblings about growing up just after World War II, Sir Paul McCartney on recruiting him because of his impressive guitar riffs, and a German couple from the band’s gritty early days in Hamburg bars are about all that’s new here. As a devoted “George girl” who followed his every note since the group’s first 45 was spun in the States, I was disappointed not to hear more about his musical influences, other than Eric Clapton’s comment about his blending the blues and rockabilly. (The interviews were conducted by Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame and Museum curator singer/songwriter Warren Zanes.) But the second half, about Harrison’s post-Beatle years after 1970, that were somewhat less in the public spotlight, is far more informative and insightful, emphasizing that his desire to leave the band to explore his own creativity paralleled his lack of interest in making more money. This period also coincided with his long marriage to (the very tolerant) Olivia, a producer of the film, who is extensively interviewed about his spiritual and personal quests, and notably about the nightmare of the crazed attacker they fought in 1999. Even if the background about the first all-star benefit concert (for Bangladesh) in 1971, Monty Python’s film Life of Brian (1979), and the Traveling Wilburys super-group recordings in the 1980s are familiar, the relaxed home movies of his architectural restoration and plantings of his grand estate, Friar Park, and anecdotes from his collaborators are charming, such as Tom Petty on his collaborator’s ukulele collection. Ringo Starr even turns his tears about Harrison’s final illness in 2001 into a wry Beatlesque chuckle.

Andrew Bird: Fever Year captures one year on the road of an idiosyncratic musician, who’s usually filed under “indie rock,” at the culmination of a 2009 tour of 166 shows so intense that Bird worked himself into a fever. What is lost here is his artistic development as he perfected his multi-instrumental looping techniques of channeling many different genres from electronica to Americana to jazz; I was at an early performance with a small, restless audience impatient with his solo experimentation. There is little personal revealed about him, except when relatives visit backstage and his obvious regeneration when he retreats to his Illinois family farm. While director Xan Aranda collaborated with Bird in the past on music videos and stage projections, this documentary was conceived on the farmhouse porch at the end of their five year relationship, and he clearly trusted her to stay focused on how he builds layers for a performance, from very poetic lyrics to the distinctive horns.

If you haven’t already read W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn (1992), seeing Grant Gee’s adoring and elucidating Patience (After Sebald) will make you want to walk to the nearest book outlet. If you already read the uncategorizable book (his publisher chuckles here about what section to tell stores to put it—novel? travel? philosophy?), you will appreciate how Gee, as a fanboy, follows Sebald’s steps around the eastern coast of England and delves into the author’s stream-of-consciousness discursions on (at least) millennia of history, technology, genocide, and nature. Gee used his commission from “The Re-Enchantment,” a British project exploring relationships to places through art, to film Sebald’s possibly fictional character in real landscapes. Besides the striking black-and-white visuals that re-create what Sebald illustrated from his walks, Gee adds to the detailed geographical footnotes (available online) by probing the implications of Sebald’s language that helps to make this much more than a cinematic CliffsNotes. (Jonathan Pryce reads the excerpts.) As a German writing in his native language while teaching at a British university, Sebald’s works frequently considered the ironic traces of war between Germany and England, and went largely ignored until his works were translated into English. Gee’s unabashed enthusiasm could encourage more to not only read Sebald, but walk in his footsteps.

Leave A Comment