There are many reasons why this animated Latvian film about a cat and an unlikely group of animals surviving a massive flood is a crowd-pleaser. Certainly, there is the warmth of its message, which will appeal to many in an especially dark year. There is also the immersive quality of its animation, with stunning details in water reflections, underwater scenes, and on tree trunks. Additionally, the way the image zooms and rotates, like an animal finding its way through the wilderness, adds to its depth. The animators have strikingly imitated the exact movements of the animals—the cat, in particular, is an astonishing piece of work.

Greater than all of this, however, is the movie’s surprising poetry. An apocalypse of sorts has occurred, but without any clear moral angle: Humans have gone, but it is neither clear nor important exactly why. When the cat falls through the water and finds itself swimming among the tops of submerged trees, when mountains and palazzos sink in the rising water, and a beached whale lies dying in the forest after the flood has passed, it is difficult not to feel a sense of awe—something I was completely unprepared for. Flow takes us to incredible places and sights. Andrew Plimpton (In theaters)

The fall of Syria’s dictatorship and the second coming of President-elect Donald Trump have stirred up controversy around the already contentious subject of immigration. Though centered on real-life events in Eastern Europe in 2021, Polish director Agnieszka Holland’s harrowing Green Border feels timelier than ever. The film offers a comprehensive perspective on undocumented migration, exploring it from multiple angles.

Young and old immigrants from Syria, Afghanistan, and Sub-Saharan Africa plead for mercy in dense forests as jeering border guards forcibly push them back and forth between Poland and Belarus, both countries creating Catch-22 bureaucratic obstacles to deny them entry. Border personnel grapple with bruised consciences and strained personal relationships due to their duties. Meanwhile, activists argue among themselves as they fight mostly losing battles for immigrants’ rights.

The stark black-and-white cinematography, chaotic handheld camerawork, and raw, anguished performances highlight the human cost of immigration. The film portrays misery, cruelty, and callous indifference to human life with unflinching clarity. While emotions run high, the film delivers a cold, stoic message: There are few havens for the masses of displaced people. Most places resist their arrival, and no appeal to reason or kindness seems likely to change that. Caroline Ely (Streaming on multiple platforms)

Richard Linklater’s Hit Man is a lot of things. An unorthodox crime drama. An unexpectedly sexy romantic comedy. A quasi-true story inspired by a Texas Monthly article about the real-life teacher-turned-fake-hit man Gary Johnson, spun out in a slightly more absurdist direction. But above all, Hit Man is a LOT of fun. (Sadly, this Netflix-distributed movie deserved more time in theaters before its streaming release.)

Beyond Linklater’s direction, the real star here is actor/co-writer Glen Powell, who’s certainly having a moment with this, Top Gun: Maverick, Anyone but You, and Twisters. Despite his profoundly ordinary name, Gary Johnson is the ultimate test of Powell’s acting prowess. He constantly shifts between the mild-mannered psychology teacher (his day job) and various hitman personas, hilariously assisting the police in stopping would-be murderers by convincing them he’s the right man for their crimes.

One of those personas, the suave heartthrob Ron, just so happens to talk abused wife Madison (Adria Arjona) out of going through with one such plan—only for that kindness to morph into a sexual relationship. Gary is drawn to Madison, but she falls for the fake “Ron.” Powell and Arjona’s chemistry is truly off the charts, but it’s the way Hit Man builds tension around this screwball noir dynamic, as Gary’s two worlds collide, that makes the story unpredictable yet deeply engaging.

If anything, it’s proof that Hollywood should fully embrace Powell’s leading-man status moving forward. Ben Wasserman (Netflix)

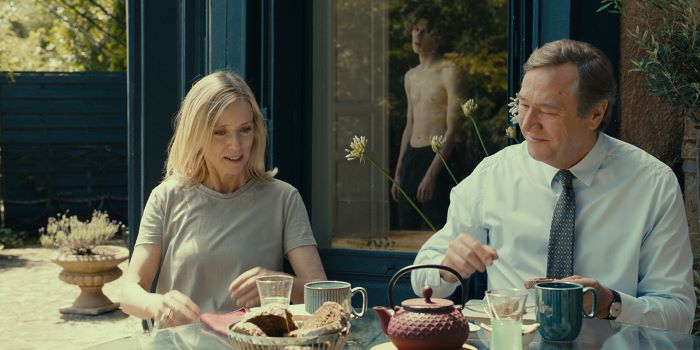

More than halfway through Last Summer, a scene features a confrontation between Pierre (Olivier Rabourdin), his teenage son, Theo (Samuel Kircher), and his wife Anne (Léa Drucker), with whom Theo has been having an affair. The two adults in the room face the child with cold, steely expressions and tight jaws. The boy, as soon as he hears what they have to say, starts shaking and struggling to breathe. It is not the only time that we see someone react like this. We see characters do it under relentless questioning or after sex. Viewers may find themselves gasping the same way by the time the credits roll.

Though this is far from the first time in her long career that director Catherine Breillat has broken taboos, explored a sexual relationship with a massive age gap, or created a venue for our darkest impulses (or all of the above), it is remarkable how she has kept her films fresh while feeding similar obsessions. Here, the bourgeois facade of peace, stability, and civic responsibility is inextricably entwined with a darkness that springs from the complete absence of restraint. It also stands at a compelling angle to a loose group of recent movies (Anatomy of a Fall, Saint Omer, and May December) that dramatize how information can be weaponized and mishandled when we are given a partial view of a disturbing situation. In Last Summer, the truth is known, and viewers are privy to the various ways it is suppressed, finding themselves in a similar state of near breathless discomfort by the end of this deeply unsettling film. AP (Criterion Channel and multiple platforms)

The bond between Yuval Abraham, an Israeli journalist, and Basel Adra, a Palestinian activist, is one of the most moving elements in their sobering and concise documentary (co-directed by Hamdan Ballal and Rachel Szor). Amid the expulsion of residents and the destruction of homes, schools, and infrastructure in Adra’s West Bank Palestinian community by the Israeli military, the two men reflect on their lives and mission at the end of the day. Abraham strives to get his stories out quickly on social media, while Adra gently chides him, calling him “too enthusiastic.” Adra carries the weight of decades of struggle and the pain of his people, long ignored by world media, whereas Abraham, though well-meaning, remains an outsider.

The two men, both in their mid-20s, are united in their fight for justice but divided by seemingly banal distinctions, such as the colors of their license plates. Abraham’s yellow Israeli plate grants him the ability to travel freely across the region, while Adra, restricted to the West Bank, has no such privilege.

The film, shot between 2019 and October 2023, feels like a lightning bolt amid the current landscape of Israel’s war on Gaza. It cannot hope to capture the full scope of that crisis or the vast history of conflict. Instead, it focuses intently on a few individuals, including a woman living in a cave-like space as she cares for her son, who was shot by the military. The documentary’s strong points of view form a powerful political picture, one that has the potential to change and deepen perspectives. Maddeningly, however, despite its acclaim, it has yet to find a theatrical distributor. Jeffery Berg (Playing in select theaters)

Mohammad Rasoulof’s captivating film follows a family in Tehran amid the mounting “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests against the Iranian government. Rasoulof’s well-crafted script continuously subverts expectations. What begins as the father’s story soon shifts focus to his wife and two teenage daughters. (A civil servant, he has just been promoted to the position of investigative judge within the legal hierarchy.) As the protests outside the cocoon of their apartment escalate, the delicate complexity of the sisters’ relationship with their more conservative mother unravels.

Since Rasoulof, now living in exile in Europe, had to shoot the movie in secret to avoid persecution, it reveals creative ways of working within limitations. Clips of real phone footage are effectively woven into the narrative. In one striking sequence, a fictional shot of the mother driving onto a road where onlookers shout at her to turn around suddenly cuts to real footage of protesters being attacked on what might be the same street.

When a gun goes missing, the story takes on the tone of a breakneck thriller in its twisty final act, deepening its themes of paranoia and distrust. At first, Rasoulof’s shift to another genre with its melodramatic swings may feel abrupt. Yet, because we’ve come to know this family so well, the conclusion becomes incredibly involving. The film culminates in a tense, almost operatic sequence of chaos—and perhaps a family’s rebirth. JB (In theaters)

Violence and crime tend to perpetuate and deeply corrupt communities where fear reigns supreme and impunity thrives. This is the morally ambiguous world introduced by Sujo, the Mexican film co-written and co-directed by Fernanda Valadez and Astrid Rondero. The story closely follows the coming-of-age of the son of a sicario (hitman) after his father is killed as a traitor to his gang. Orphaned at the age of four, he is raised in an atmosphere of austerity and fear by his benevolent aunt. However, a decade later, the boy seems destined to follow in his father’s footsteps, as the “legend” of his progenitor haunts him during his teenage years. Unlike his father, can he break free from a life of delinquency?

Valadez and Rondero have crafted a narrative and visual antidote to the seductive portrayals of violence so common in Mexican news and media. Here, violence is mostly relegated to an off-screen echo—its consequences linger, but it is not the central focus. Instead, the movie becomes a humanizing journey of individual progress, as Sujo attempts to rise above his circumstances, all without indulging in fairy-tale resolutions.

Sujo is further distinguished by a tapestry of evocative imagery and enveloping camerawork, treating both dreamlike visions and harsh realities with equal seriousness. Brilliant in its narrative economy, the film stands out as the latest example of the rejuvenation happening in independent Mexican cinema, skillfully blending social awareness and spirituality. Through the collaboration of its two female filmmakers, Sujo confronts the open wounds of the nation—its contemporary history riddled with injustices—and addresses them with grace. Guillermo Lopez Meza (In limited release)

Like the bastard child of filmmakers Stuart Gordon and Nicholas Winding Refn, director/writer Coralie Fargeat presents a body-horror morality tale for the ages. Demi Moore stars as Elizabeth Sparkle, a former actress turned fit, fabulous, and famous aerobics TV show instructor. When she overhears executive Harvey (a hysterically amped-up Dennis Quaid) plotting to replace her with a younger host—on her birthday, no less—she becomes distraught.

After a minor car accident, an attending nurse slyly hands her a thumb drive. On it is a commercial for the Substance. By injecting the product, you can become your younger self—but only for a week at a time. From this premise emerges an over-the-top, biting satire of vanity and the male gaze. As Elizabeth and her younger self, Sue (Margaret Qualley), vie for time and attention, their bodies begin to deteriorate and mutate, leading to a climax that practically dares the finale of Dead Alive to hold its beer.

Sleekly shot with bright, pastel colors and plenty of empty space for Elizabeth to exist in solitude, The Substance is not subtle in its commentary, but it is certainly spot-on. Pulling the film’s disparate elements together is a lovely, grounded performance by Moore, who, with few words, draws you into Elizabeth’s glamorous yet profoundly lonely life. And what is the titular substance that brings such misery? As my wife said after watching the film: society itself. Paul Weissman (MUBI and multiple platforms)

Terrestrial Verses

Clear. Concise. Devastating. Written and directed by filmmakers Ali Asgari and Alireza Khatami, Terrestrial Verses presents a litany of restrictions and cruelties that ordinary citizens face in the Islamic Republic of Iran. A series of vignettes dramatizes the efforts of bureaucrats to discipline Tehran residents for their wrongful ways. These include naming a newborn “David,” a Western and therefore unauthorized option; driving without a hijab (as captured on CCTV); and applying for a driver’s license while bearing concealed tattoos.

Each nuanced segment could be a one-act play, presenting a unique battle against totalitarian and fundamentalist rulings—and the officials who exploit their superior roles. These authority figures interrogate their subjects off-camera, so the focus remains on the persecuted individuals, who first attempt to reason with them, then defend themselves. This eventually turns into exasperation and outrage, escalating to such absurd extremes that the film becomes a tragicomedy. In 77 effective minutes, the fine cast represents people from all walks of life, in a society crushed by the powers that be. Rania Richardson (Criterion Channel, Prime Video)

The Wild Robot is a family film in the best sense of the word. It is pointless to do anything but walk right into the massive hug it seeks to enfold the viewer with. At a time when many are expressing concern about the influence of AI, this animated movie paints a more optimistic picture of the relationship between machines and nature. The optimism, however, depends on one thing: the machine’s ability to go off script.

After a storm, a robot (voiced by Lupita Nyong’o) crash-lands on an island, fully ready to assist the humans she’s been programmed to serve, but unable to find any for miles. Instead, she is surrounded by a group of wild animals who have neither use for nor trust in her. This changes, on several fronts, when ROZZUM 7134 (soon to be called “Roz”) accidentally destroys a goose nest and is inadvertently tasked with raising an orphaned gosling. A mischievous but soft-hearted fox (Pedro Pascal) inveigles himself into Roz’s household, theoretically to reap the benefits of a hyper-capable robot companion, but ultimately, he cares as much for the young gosling as she does. Everyone—robot, fox, and the whole woodland crew—ends up abandoning their natural (or programmed) inclinations for something greater.

There are certainly tear-jerking moments, and the whole thrust of the storyline is appropriately moving. Yet many of the best parts of this film involve the colorful cast of woodland critters and the comical misunderstandings between animal and machine. A group of possums, in particular, provides an especially successful series of gags revolving around one of the animal’s chief talents—playing dead. AW (Multiple platforms)

Leave A Comment