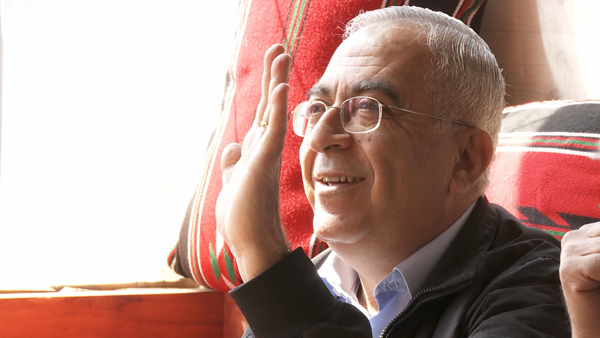

The Gatekeepers last year revealed a consensus for a two-state solution with the Palestinians among the intelligence chiefs who had been in charge of Israel’s security. Now it seems like the next step should be for someone on the other side to roll up their sleeves and help get it done. Israeli documentarian Dan Setton thought he saw just the guy to do it when Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad began work on his practical 2009 plan “Palestine: Ending the Occupation, Establishing the State” to convince the United Nations that Palestine was ready to become the 194th member nation. State 194 follows him and others on both sides of the divide who are taking concrete steps to succeed. With events overtaking the film after its completion, this optimism is even more bittersweet.

But it’s still worth seeing for an insider’s look at nonviolent Palestinian activism, too rarely seen in films. Fayyad, appointed by Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, is an economist who served a stint with the International Monetary Fund. First seen traveling the world to secure loans, he’s followed in verité style as puts the funds to work—“step by step, brick by brick”—on substantive capital development projects appropriate for a well-run state, such as expanding the electricity grid, opening a rural health center, and building chambers for the Palestinian Authority legislature.

Younger voices from a burgeoning civil society represent the Palestinian version of the Arab Spring. They use social media for outreach, especially across the divide between the West Bank under Fatah’s control, in the person of an urbane, secular young woman, blogger Madj Biltaji, and Mahmoud El-Madawi, who has to deal with the religious and political censorship by Hamas in Gaza. Their conviction that posting online is equal to the tough work of community organizing is a naïve misrepresentation of the Egyptian revolution’s outcome, but they help generate a similar temporary excitement when, in March 2011, large crowds demonstrate for unity between the two main political parties. The leaders of both sides quickly respond by issuing some unity rhetoric, but with no concrete action, the rest of the world, particularly the Security Council, remains unconvinced they will implement shared governance.

Other activists are more familiar, either specifically or as types: Palestinians and Israelis who have been personally affected by the continued violence but are working together on peace and nonviolent challenges to encroaching Jewish settlements and the separation wall’s construction. Such have been seen in documentaries including Julia Bacha’s Budrus (2009), though at least it’s hopeful that such efforts persist against the taunts and opposition seen here.

The U.S. role, though, is confusingly over-emphasized through Washington lobbyists as competing influencers on government policy. The powerhouse AIPAC-American Israel Public Affairs Committee’s support of Israeli government positions is presumed by a clip of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu addressing their huge annual meeting, but it’s not made clear that the small alternative J Street is its counterpoint, whose Israeli-born founder Jeremy Ben-Ami is unnecessarily tracked through the halls of Congress and at home with his family.

Hopes are dashed with the updated denouement scroll that the Security Council continues to avoid giving Palestine recognition, that the General Assembly has granted the Palestinian Authority non-Member Observer State Status just like the PLO before it, and, defeated, Fayyad resigned last month. But his efforts, and of the other cock-eyed optimists, are worth being seen so they won’t be forgotten under the usual media onslaught of the louder preventers of peace.

Leave A Comment