It’s been more than a hundred years since her heyday, but is Loie Fuller enjoying a new turn in the spotlight from beyond the grave? The dancer and innovator occupies the center of Sabine Krayenbühl and Zeva Oelbaum’s documentary, which makes a compelling case for her as a visionary and a pioneer in early technology.

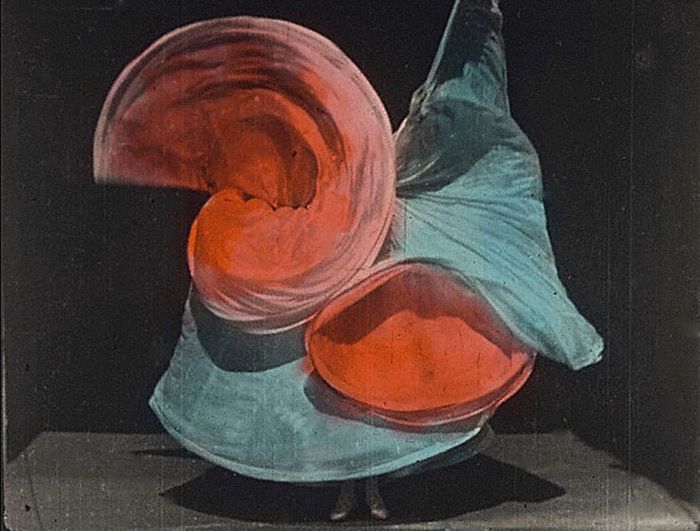

There’s merit to that claim. Colorized footage highlights the Illinois-born Fuller performing her famed Serpentine Dance, a choreographed spectacle combining light effects, movement, and swirling cloths mounted on sticks. Fuller—and later enactors of the dance—resembles fairies, fireflies, or bats. It’s easy to see why her work captured the imagination of artists such as Auguste Rodin and still elicits accolades from contemporary figures like choreographer Bill T. Jones and director Robert Wilson.

Light emerges as a central theme of Fuller’s artistic career. Her use of then-revolutionary electric lighting set her apart from her contemporaries, lending an ethereal, flickering quality to her performances. Her experiments with light sources even led to a partnership with Marie Curie, which famously ended in a radium explosion that burned off Fuller’s hair. Friend, rival, and frenemy Isadora Duncan grudgingly admitted of Fuller: “She was not a great dancer, and she had a dumpy little body, but her lighting effects and her mirror effects … were simply out of this world!”

Despite her high-concept experiments, Fuller comes across as a grounded, relatable figure. Isadora Duncan was correct—the proud Midwesterner did not possess a dancer’s sylphlike poise or noble expression. Instead, she worked magic with her athletic physicality and engaging, expressive face. She delighted in telling down-to-earth stories about her humble origins, made even more charming by Cherry Jones’s folksy narration: “In Berlin, I had to dance in a circus between an educated donkey and an elephant that played the organ. My humiliation was complete!” Fuller’s practical, levelheaded approach endeared her to the public, while her conviction that “dance needs to stand for something” gave her an artistic purpose.

The documentary, however, risks over-egging the pudding in persuading viewers of Fuller’s influence and legacy. Designers, choreographers, and even Taylor Swift (in a brief concert clip) are cited as being inspired by her. The filmmakers seem eager to name-check as many art-world figures as possible, and on the narrative track, Fuller herself boasts of encounters with luminaries like Thomas Edison. At times, the tame piano music and vintage footage can make the documentary feel a little stodgy. Modern reenactments inject some much-needed energy, including a triumphant Fuller-inspired dance performed by Shakira in concert.

Ultimately, Fuller emerges as a figure of hard work, artistic faith, and a profound understanding of the rewards and challenges of creative expression. In capturing the breadth of Fuller’s accomplishments, Krayenbühl and Oelbaum succeed in inviting a fresh reassessment of this remarkable and influential artist.

Leave A Comment