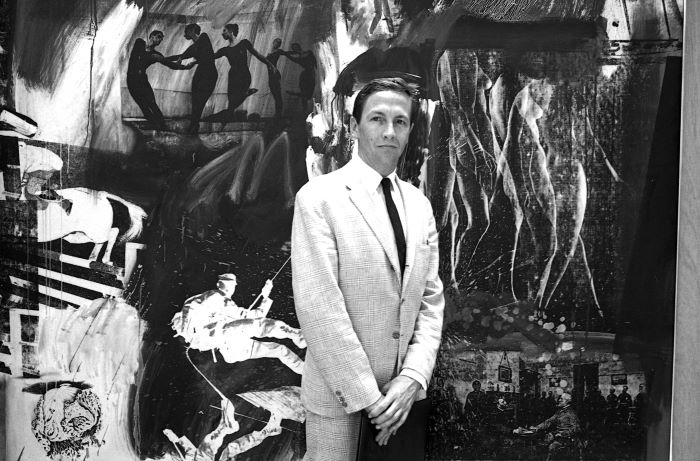

Robert Rauschenberg in front of his painting Express at the1965 Venice Biennale (Ugo Mulas/Zeitgeist Films in association with Kino Lorber)

In 1964, the United States was simultaneously fighting a Cold War with the Communist bloc, competing in a burgeoning space race with the Soviet Union, and still mourning the shocking assassination of President John F. Kennedy. In other words, as Amei Wallach’s documentary breezily makes clear, the time was right for art and politics to mix at that year’s Venice Biennale, the prestigious biannual exhibition that hands out prizes to artists who accept on behalf of their countries.

The U.S. government was never interested in the results of the Biennale before, but current events conspired to force its hand, using culture to combat communism. When Alice Denney—a friend of the Kennedys and a perfectly positioned Washington cultural maven—was tasked with finding a commissioner for the U.S. delegation at the Biennale, she zeroed in on critic and curator Alan Solomon. As the head of New York’s Jewish Museum, Solomon had recently presented an exhibit by Robert Rauschenberg, one of the world’s leading pop artists, along with Andy Warhol and Rauschenberg’s then-lover, Jasper Johns. It wasn’t surprising then that Solomon ensured that Rauschenberg was among the artists displayed at the Biennale’s U.S. pavilion. (The others that year included Johns and the recently deceased Frank Stella.)

Taking Venice is shrewdly paced like a thriller, with pulse-pounding music accompanying the unfolding narrative. Interviews, both vintage and new, with Rauschenberg, Solomon, Denney, and other art experts and historians are featured as Wallach cleverly constructs a mystery: Will Rauschenberg actually win? The often breathless maneuvering of the U.S. delegation came to a head after the realization that the Biennale’s rules were not being followed: Only one of Rauschenberg’s massive silkscreen paintings was hanging in the official U.S. pavilion. So, Solomon and his team came up with a clever solution.

Parallel to Wallach recounting the manipulations that took over the Biennale, the director also presents a primer on Rauschenberg’s art and career. Though the Port Arthur, Texas, native was initially derided as a lightweight, since his art comprised a mix of everyday objects and pop-culture imagery, he deftly handled such materials to make pertinent cultural statements without condescension or pretension.

Rauschenberg was also multifaceted, working closely with choreographer Merce Cunningham and composer John Cage to create dazzling designs and colorful costumes for their modern-dance pieces. In fact, Rauschenberg arrived in Venice to attend a Cunningham troupe appearance during the Biennale, which became another piece of evidence for those who thought that the competition was fixed.

Rauschenberg wasn’t comfortable with nationalism as part of a contest pitting artists against one another. It’s probably just coincidental, but nonetheless noteworthy, that his art turned darker and more political following the Biennale as it took on subjects that colored American society later in the decade. Wallach sensitively touches further on the subject of nationalism through the words of a more recent American artist, Simone Leigh, who expresses her complicated feelings as the first Black female artist to represent the U.S. at the Biennale.

Taking Venice is an engaging journey back to an era when art became as serious a business as politics.

Leave A Comment