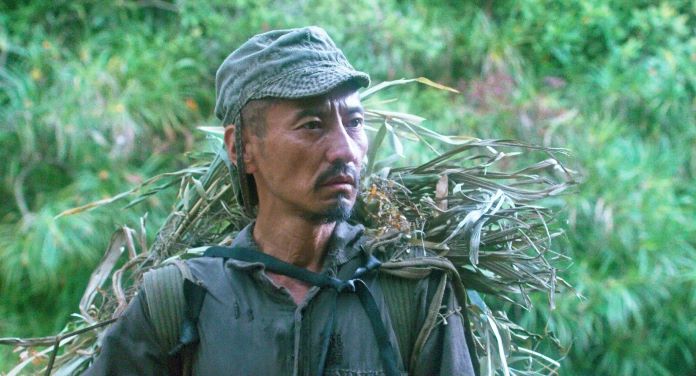

We first see Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda (Kanji Tsuda) by himself in the forest on Lubang Island in the Philippines. His hair is beginning to gray. He carries a rifle and wears a camouflage blanket made of grass on his back, making him look like something half human, half plant. The year is 1974, and he wears a military uniform. He lives his life as though World War II is still raging.

We then zip back to 1944, where we see a younger Onoda (Yuya Endo) dead drunk in a bar, where he is approached by Major Taniguchi (Issey Ogata). Onoda has failed to become a pilot because he is afraid of heights, but the major is determined to give him another chance. Soon, Onoda is overseas as a lieutenant in the Japanese-occupied Philippines, approaching his tasks with a fervor that some of his fellow officers find off-putting. After they are attacked and forced into the jungle, Onoda commands a dwindling number of soldiers and insists they will hold out and fight for their country. Eventually, he is in charge of just three men as others die or flee. We know already that he will be the last one standing.

Onoda, directed by Arthur Harari, is based on a true story, and it’s quite an undertaking. Harari ambitiously seeks to encapsulate Onoda’s entire stay on the island, and the result is well paced. While much of the action involves daily struggles, the story line is balanced with more climactic events: deaths, attacks, near-lapses in faith, fights, and reconciliations. More than once, Onoda has a chance to learn that the war is over, only to choose not to trust what he hears, believing it to be a conspiracy created by his enemies. The film is nearly three hours long, covers 30 years, and there is rarely a dry stretch. Add to this, the cinematography beautifully captures the Filipino countryside, sometimes depicting the men against vast landscapes in a way that dimly recalls Mizoguchi.

Perhaps most impressive here is the mixture of tones. Throughout we see multiple dimensions in Onoda’s endeavor: comic, tragic, perverse, noble. Onoda, from the moment he arrives in the Philippines, is consumed by a dedication to his work that transcends reason, though it is unclear exactly why. Possibly, there is a sense of shame that he came to the war so late. Nevertheless, through the camera’s detached gaze, we never view him in the same light, and though he can have our sympathy, many of his acts are horrifying: A number of innocent people die at his hands when we know the war to be over and he either does not accept or has turned away from the truth.

In spite of these strengths, the movie does not feel perfectly sustained. On one hand, certain characters, even if they are taken from real life, such as the tourist who finds Onoda toward the end, are not well realized and feel more like plot devices. The chief flaw, though, might be Harari’s conception of Onoda. In spite of the multiple angles from which we view him, his story is plagued by gaps. A section that involves the specialized military training he received is not adequately explained, nor does it really seem like training—it looks much more like students learning school lessons. The story may, in fact, lose itself in too much action, at the expense of Onoda’s emotional life. Even if we have answers as to why and how Onoda managed to do what he did, and get a few powerful scenes in which his character really comes alive, there is still something lacking, as though it were missing an essential, animating spirit.

Onoda wrote a book about his experience, titled No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War (1999). In the press notes, Harari mentions that he did not discover this book until he had already finished the script. He was glad of this, he says, because it gave him the freedom to invent the character as he chose and not to be “a prisoner of [Onoda’s] subjectivity.” Perhaps he was right to, but one can’t help but wonder if he would have delivered a more sustained and compelling film had he immersed himself more fully in his central character.

Leave A Comment