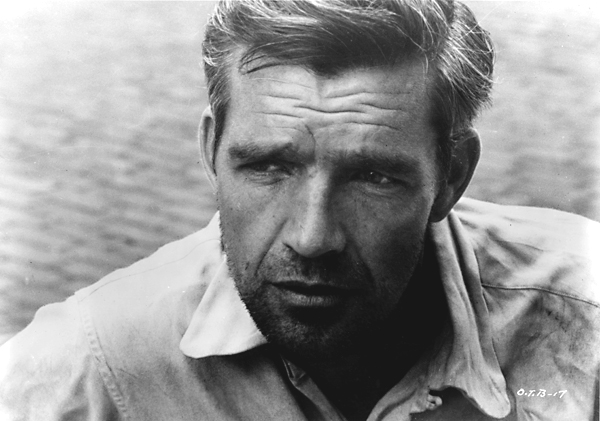

Ray Salyer in ON THE BOWERY (Milestone Films)

![]() Before there were homeless living on city streets, there were “Bowery bums” drinking, sleeping, and panhandling on a notorious stretch of lower Manhattan. In the late 1950’s, Lionel Rogosin hung out with them for six months, gained the trust of these Runyon-esque guides to New York City’s skid row, and shaped a narrative around their lives with unusual sensitivity. The restoration of his On the Bowery, which he independently released in 1957, is fascinating for urban and film historians, but it’s also a moving tribute to the timeless power of film to illuminate social issues.

Before there were homeless living on city streets, there were “Bowery bums” drinking, sleeping, and panhandling on a notorious stretch of lower Manhattan. In the late 1950’s, Lionel Rogosin hung out with them for six months, gained the trust of these Runyon-esque guides to New York City’s skid row, and shaped a narrative around their lives with unusual sensitivity. The restoration of his On the Bowery, which he independently released in 1957, is fascinating for urban and film historians, but it’s also a moving tribute to the timeless power of film to illuminate social issues.

On the Bowery pans the gritty neighborhood in summer’s heat, just before the dark, noisy Third Avenue Elevated train was dismantled, to gradually focus on three men over three days, each portraying a version of himself, improvising dialogue redolent with period and local slang. New to town, Ray (Ray Salyer) is younger and healthier than many of the others, and better dressed. Looking around for familiar faces from his days working on the railroad, he treats the older, garrulous raconteur Gorman (Gorman Hendricks) to rounds of his favorite drink, and Gorman, in turn, shows him the ropes. The life of a day laborer then looks a lot like the shape-ups illegal immigrants face today, but the truck unloading takes place in the now-gentrified meatpacking district and just down Houston Street from Film Forum, where this beautiful black-and-white restoration (by the Cineteca del Comune di Bologna) is premiering. As both men start sinking into a boozy haze, they encounter Frank (Frank Matthews), who recounts his experiences in and out of the drunk tank and scrounges around the Bowery to find anything worth selling.

This unstinting view of the ravages of alcoholism goes beyond the fiction of Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend (1945) and Blake Edwards’ Days of Wine and Roses (1962), especially in showing a whole community catering to alcoholics. There’s the bars serving cheap booze, the pawn shops (and Gorman has no compunction stealing Ray’s battered suitcase), sidewalks littered with people sleeping off binges, infested flop-houses, and the dingy single-room-occupancy hotels that were only a step up. The glimpses of the few women on the Bowery are especially heart-rending for their vulnerability; the crowded Bowery Mission, with its clean sheets and hot meals in exchange for religious exhortations to stay sober, is available only to a long line of men. (My first college internship was working with a housing agency trying to figure out how to help the elderly remnants of this population, with all their frustratingly multiple problems.) While there’s a climactic, celebratory saloon scene where the Bowery residents relish spending their day’s earnings in a more and more boisterous bacchanal, the many montages of drunken and hung-over faces, particularly at the end, poignantly bear evidence of their hard lives.

Selected for the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 2008, On the Bowery would probably not now be considered a documentary, though it garnered an Oscar nomination in that category. It was made in the spirit of filmmakers who inspired Rogosin—how Robert Flaherty combined fiction and anthropology in such early films as Nanook of the North (1922) and the Italian neorealist Roberto Rossellini incorporated the local fishermen and setting into Stromboli (1950). This blurring of categories for the essence of realism was similarly employed several years later by Kent Mackenzie in the recently restored The Exiles about Native Americans in Los Angeles that Milestone Films distributed two years ago.

Watching the film raises a host of “How’d they do that?” questions—as to the filmmakers’ relationship with the cast, what is vérité, and what is staged or reconstructed. Many of the answers are in the accompanying new documentary “The Perfect Team: The Making of On the Bowery,” directed by Lionel Rogosin’s son, Michael. In addition to providing background on the history of the Bowery and sociological context, there are insightful interviews with his late father, colleagues, and family members of the filmmakers, including renowned historian Gerda Lerner, the widow of Bowery’s editor Carl Lerner.

Lionel Rogosin stresses how the horrors of World War II shaped his determination to engage in social cinema, focusing on living conditions just a few blocks from where he and other artists lived in the West Village (and drank heavily in slightly more upscale bars). European film historians note that On the Bowery was even more influential overseas, where it became a Cold War tool to either criticize the U.S. or tout the American freedom to criticize, depending on point of view.

Also included are clips from the cast’s appearances on TV shows, where Ray Salyer, looking every inch the potential Gary Cooper-esque movie star, articulately describes the working men of the Bowery, even while he stubbornly defends his right to be an alcoholic. Rogosin’s dedication of the film to Gorman Hendricks is put in sharp relief with the revelation that while he acceded to the filmmakers’ demands to stay mostly sober during the four-month shoot, he went on a bender right afterward that killed him.

With its vivid portrayal of addiction and of a society uninterested in its damaged war veterans and older manual laborers who can’t adapt to changing work requirements, On the Bowery is soberly contemporary. September 17, 2010

Other DVD Extras: As part of Milestone’s continuing focus on the restored works of director Lionel Rogosin, the supplements to On the Bowery provide useful background on the man and the neighborhood. In addition to the essential “The Perfect Team: The Making of On the Bowery,” three shorts provide historical and contemporary perspectives and emphasize the sensitivity of Rogosin’s achievement. “Street of Forgotten Men” crams a lot of negative stereotypes about the hopeless “sodden souls” into a two-minute Columbia Pictures newsreel from 1933. The condescending narrator’s claim to be sympathetic is belied by the attention on “Mr. Zero,” a quite different approach from Rogosin’s individuation. So it’s startling how little had changed for alcoholic men at “The Bowery Men’s Shelter” in 1972, as seen in this 10-minute tour originally produced for local public television, other than the government taking over from the mission seen in Rogosin’s film and bureaucracy replacing sermonizing. The most notable change is seen in Michael Rogosin’s 12-minute “A Walk Through the Bowery” (2009). A historian and other guides show the tremendous impact of gentrification on the neighborhood, which is no longer skid row or even the cheap digs for writers and musicians of the 1960s.

On a second disc, Rogosin’s politics and motivations are delineated in his 1964 film Good Times, Wonderful Times and its accompanying making-of, “Man’s Peril.” While it is an anti-war and anti-nuclear diatribe, the collection of man’s inhumanity-to-man footage for this 69-minute film is extraordinary, from Hitler Youth rallies juxtaposed with the German army freezing to death in Russia to radiation victims in Hiroshima—still powerful even after all these years of History Channel World War II programs. Most intriguing is the framing device Rogosin created to challenge his audience. The rise of fascism and the resulting horrors are interspersed with a swinging London cocktail party that seems straight out of a Mad Men episode. Rogosin inserted a sexy art student as an agent provocateur to initiate politically provocative conversations into a smoke-filled gathering of suits recruited from ad agencies and their flirtatious wives. As the liquor flows, the apathetic veterans of the Korean War and British colonial conflicts drown memories of their experiences, in contrast to scenes of Bertrand Russell and other activists demonstrating for nuclear disarmament and civil rights. Even as it looks like Don Draper will walk in any minute, the world is now once again trying to get governments to stop making nuclear weapons, making Rogosin’s point of view still sadly fresh.

Leave A Comment