Every year the curators at the Museum of Modern Art’s Department of Films sort through major studio releases and various film festivals to select the innovative and buzzed-about movies they believe will have a lasting impact. Now in its 12th annual incarnation, MoMA’s “The Contenders” series (running through January 8) screens some of the most noteworthy films of the previous 12 months.

The 2019 class of contenders includes acclaimed titles (The Irishman, Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood, Marriage Story) that have landed on the best-of-the-year lists, earned critics’ prizes and Golden Globe nominations, and are bound to score Oscar nods as well. Yet other notable films in the series have fallen under the radar and deserve closer consideration.

With its privileged, hyper-articulate characters and intellectual setting of the Parisian publishing world, French director Olivier Assayas’s Non-Fiction, a wry comedy of manners, ideas, and romantic entanglement, will remind many of Woody Allen’s better films. It opens with elegantly handsome publisher Alain (Guillaume Canet) and his shlubby novelist friend Leonard (Vincent Macaigne) at lunch in a café discussing the future of literature in an era of social media. (“Twitter is like the Ancien Régime,” says Alain. “It’s people sharing witticisms. It’s very French.”) It’s only after the two men return to Alain’s office that Leonard learns that Alain won’t publish his new book because his thinly disguised autobiographical novels no longer sell.

What Alain doesn’t know is that Leonard has based his work on his long-running affair with Alain’s wife, Selena (an amusing Juliette Binoche), a classically trained actress now starring in a hit TV cop show. Meanwhile, Alain sleeps with his new head of digital transition, Laure (Christa Théret), who also juggles a girlfriend on the side. Oblivious to all these erotic shenanigans is Leonard’s spouse, Valérie (stand-up comic Nora Hamzawi), a left-wing political consultant who has to rescue her candidate from a sex scandal.

In a way the film’s original French title Double Vies (Double Lives) is more accurate than the English version, as these protagonists dance a roundelay of amorous deception while wittily pondering whether the digital revolution will enhance or destroy culture and art. A delectable amuse-bouche.

Elisabeth Moss’s searing performance as a self-destructive punk rocker (hello, Courtney Love!) on the decline is the main reason to see Alex Ross Perry’s atmospheric but eventually exhausting Her Smell. The Mad Men veteran plays Becky Something, the lead singer of the all-female trio Something She. In the 1990s, the band was at the top of their game, playing arenas, earning gold records, and making the cover of hip music magazines. But thanks to Becky’s out-of-control behavior, they have been reduced to touring smaller venues and clubs.

The film opens as the band finishes a set and comes off stage. While her bandmates Marielle Hell (Agyness Deyn) and Ali van der Wolff (Gayle Rankin) decompress, Becky avoids her estranged husband, Dan (Dan Stevens), and infant daughter to indulge in drugs and a faux shamanic ritual. When record label executive Howard Goodman (a subtle Eric Stoltz) proposes the band go on tour as the opening act for Zelda (Amber Heard), Becky’s response is violently vitriolic. Later in Howard’s studio, she hijacks a recording session intended for the up-and-coming Akergirls (Ashley Benson, Dylan Gelula, and Cara Delevingne) by tinkering around in a drug-induced daze.

As she continues to alienate the people around her, including her mother (an almost unrecognizable Virginia Madsen), the emotionally drained viewer, wearied by incomprehensible shouting and mumbled dialogue, begins to wonder why her behavior is tolerated. Why doesn’t Howard just drag Becky out of the studio? Strangely for a movie about rock-and-roll, there is very little music, very few scenes of Something She actually performing. Kudos, though, to cinematographer Sean Price Williams for capturing the grunginess of the backstage world with a Behind-the-Music documentary feel. You can almost smell the sweat, piss, and pot.

In the film’s middle section after Becky has finally gone through rehab and recovery, Moss brilliantly shows her range. Her once-bellicose and arrogant Becky is now chastened and ashamed, hiding out in a country house. In the film’s quietest and most tender scene, she tentatively tries to reconnect with her daughter, now six or seven, by singing Bryan Adams’s “Heaven.” Still, when Becky attempts to reconcile with her bandmates and make a comeback at the movie’s conclusion, the fatigued viewer doesn’t care very much. Becky has worn out her welcome; it’s perhaps her character’s intense abrasiveness and self-pity that has kept Moss off the short list of some major film awards.

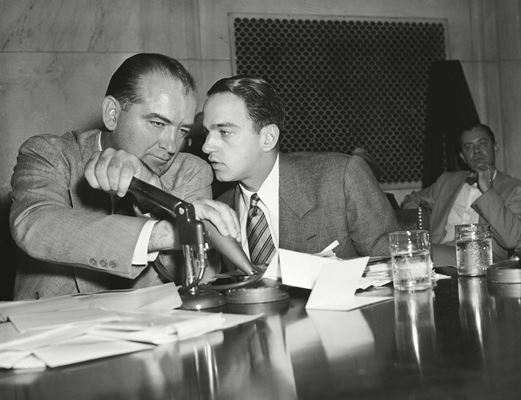

Having profiled legendary Italian fashion designer Valentino and urban activist Jane Jacobs, documentarian Matt Tyrnauer turns his attention to the notorious and inscrutable New York lawyer Roy Cohn. Taking his film’s title, Where’s My Roy Cohn? from Donald Trump’s comment on what he wanted in an attorney general, Tyrnauer traces the life of a brilliant but amoral young lawyer and a closeted homosexual who nevertheless hounded gay government employees out of their jobs while favoring his own handsome protégés (the more Nordic-looking, the better) and working for Sen. Joseph McCarthy during the 1950s Red Scare.

Despite McCarthy’s fall from grace, Cohn survived unscathed and went on to thrive in 1960s and 1970s New York, taking on such clients as mobsters and Queens developers Fred and Donald Trump who were fighting charges of violating the Fair Housing Act. He also enjoyed a flamboyant social life, lavishly entertaining celebrity guests at his East Side townhouse (strangely populated with stuffed toys, in particular frogs) and frequenting nightclubs in the company of pretty young men and the likes of Halston and Studio 54 owner Steve Rubell. It all ended in 1986 when Cohn was disbarred and he died of complications from AIDs, although he claimed his illness was liver cancer.

It’s an absorbing, appalling, and sad story, swiftly told through a series of interviews with Cohn’s relatives, rivals, former boyfriends, and one star pupil, political operative Roger Stone. But in the end this fascinating and repellant man remains unknowable. What motivated him? Who was he really beneath his hostile mask? The filmmaker digs a little bit with background details on Cohn’s remote parents, but he never really fully answers these questions. He leaves us with a chilling image of Cohn unblinkingly staring into the camera, refusing to answer an interviewer’s questions about his sexuality.

Leave A Comment