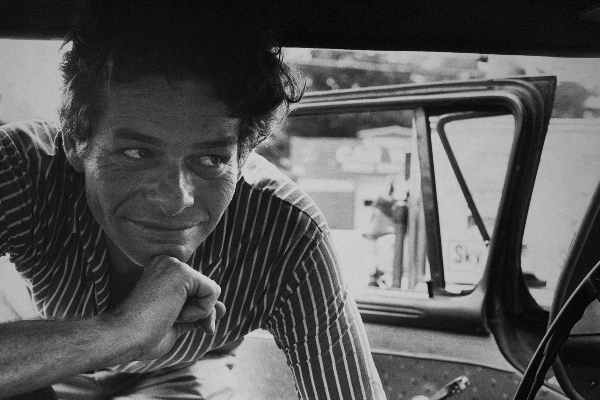

Fast-talking with a Bronx accent, photographer Garry Winogrand describes cameras early on as having the ability to tell things as they are. But the product of any camera can also tell us about the person behind it, according to this didactic, comprehensive documentary about Winogrand, who passed away in 1984, leaving behind more than 250,000 undeveloped photographs. Through interviews with a wide cross section of friends and colleagues, the film traces his career, recalling his major successes and fiascos before exploring the posthumous material.

Winogrand, whom the interviewees compare to artistic notables ranging from author Norman Mailer to choreographer and director Bob Fosse, was born to a working-class Jewish family in the Bronx in 1928. He found work as a magazine photographer while in his 20s, but he eventually gave that up for a more experimental approach to the medium. In ensuing decades, Winogrand defined what became known as street photography, shooting scenes out in public that were often ambiguous and looked chaotic. However, he had an eye for composition, and could frame the physicality of people in ways that were truly compelling. He was also drawn to less-conventional subjects for that time, such as homosexuals and minorities.

The lengthy montages make clear just how talented Winogrand was, and the film sufficiently credits him for how he pushed the limits of photography by utilizing wide-angle lenses, for example. Yet the artist himself is rarely present in the flesh to discuss his technique, save to demystify it. At one point, Winogrand demonstrates how he would flip his camera upwards to get the pictures to look a certain way, implying that his success came more from the quantity of film he shot than anything else. In precious few moments, we gain access to his most private thoughts, and so they feel revelatory. One segment delves into his composing of an artistic statement, intended for a fellowship, around the time of the Cuban missile crisis, in which he blasted the superficiality of American life and hinted at his own existential angst.

He seemed to prefer letting his work do the talking for him, and yet the film does not follow his lead and instead includes a great deal of discussion about Winogrand the artist, most of it fawning. However, there are exceptions: very different opinions abound regarding Winogrand’s 1975 book Women Are Beautiful, which collected his many photographs of women on the street. While the more negative voices decry the work as objectifying, others leap to the book’s defense, with the most compelling argument being that photography, much like any art form, should not always play it safe. Director Sasha Waters Freyer lets viewers draw their own conclusions, but either way, these scenes spice up what could have been a one-note love-in for Winogrand.

The film includes no shortage of archived footage featuring the artist in conversation, though he remains a distant figure, often making it seem as if the interviewees are using him as a tabula rasa to project their own feelings about art and the artistic process onto him. However, once Freyer gets to the treasure trove of Winogrand’s work discovered after his passing, the narrative shifts to chronicle various participants’ attempts to have these photos treated with proper curatorial respect. It’s an unexpected development, but one that is surprisingly touching as it hints that Winogrand’s legacy extends beyond just his photography, and that he was loved more than he realized.

Leave A Comment