|

Reviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

127 HOURS

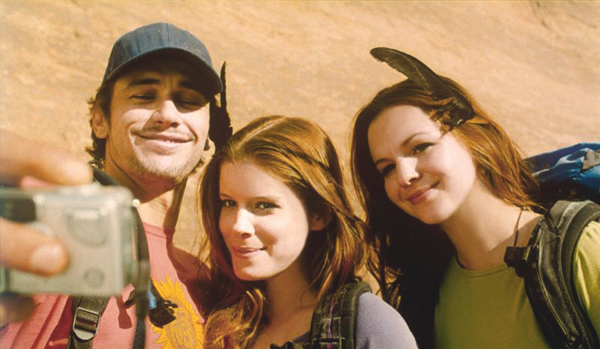

Helmed by versatile filmmaker Danny Boyle, the film documents Ralston’s headline-grabbing accident. In 2003, the 27-year-old climber slipped while scrambling up Blue John Canyon in Utah, falling several yards and getting his arm pinned beneath a boulder. Days—er, 127 hours—later, on the verge of death after having been forced to drink his own urine to survive, Ralston sawed off his trapped arm with a dull pocketknife. But that’s not all. Leaking blood and with only one arm, he managed to rappel down a cliff to safety. As was remarked at the time, the man embodies the classical masculine ideal: resourceful, tough, brave. The film, based in part on Ralston’s own account, Between a Rock and Hard Place, tries to honor those virtues by replicating the experience through Boyle’s inventive camera placement and gonzo filmmaking. Few other directors would, for example, give us a shot inside a camelback tube as urine splashes inside. 127 Hours mostly works, which is no mean feat. This is, after all, a movie essentially about one man, alone and stuck in place for five days, so Boyle deserves credit for giving it the energy, and pace, of a music video. The soundtrack helps here, too. Although Ralston is ragged in the film for liking Phish, we never hear anything so laidback. Instead, Boyle prefers pulsers like Free Blood’s “Never Hear Surf Music Again,” whose attention-getting lyrics—“There must be some kind of fucking chemical…that makes us different from animals, that makes us the same”—opens the film. But much of the weight of the picture falls on James Franco, who, as Ralston, gives the man a sort of dorky agreeableness, and whose sleepy-eyed good nature and shy intelligence make him someone most viewers won’t mind getting trapped with. Franco might be some sort of government experiment to create the perfect human being—he’s also a Yale PhD English student and performance artist and short story writer—but he deserves the acclaim he’s earned. Screenwriter Simon Beufoy (who worked with Boyle on Slumdog Millionaire) succeeds with an even trickier job, finding a way to make audible Ralston’s private thoughts. Like in Tom Hanks and the volleyball in Castaway, he cleverly provides Franco with an inanimate object to talk to—his digital camera. During recordings that serve the dual role of telling us what can’t be shown and showing us what Ralston feels, he recounts with a kind of grim, scientific precision his increasing desperation, and even puts himself on trial for selfishness. (Ralston didn’t leave a note telling anyone where he would be, which is why he knew he would not be rescued.) That said, 127 Hours is not flawless. Oftentimes, Boyle’s daring gets the better of him. During the auto-amputation scene, for instance, when the knife strikes a nerve, it triggers a buzzing sound that can only elicit inappropriate childhood memories of playing Operation. More seriously, Boyle seems not to trust the material to stand on its own. He loads the picture with numerous, largely unnecessary flashbacks of a ditched French girlfriend (Clémence Poésy) and some family home videos, as if Ralston’s ultimate struggle is not the one that made the news but rather an inner one where he has to tame his fierce need for independence. Fine, but in his effort to rise above the tale’s History Channel reenactment roots, Boyle also encumbers the last third with increasingly tiresome hallucinations, including a laugh-inducing prophecy as Ralston’s mind goes wacky from thirst, hunger, and pain. (I won’t spoil it, but let’s just say it’s the exact opposite of the dead baby vision in Boyle’s Trainspotting.)

But squeamish types, have no fear. Although the movie

comes trailing classic buzz-generating rumors of audience members

fainting during preview screenings, the arm-cutting scene manages the

impossible: it’s both unflinching and discreet.

Brendon Nafziger

|